|

December 2007-

February 2008

|

BLACK

HORSE EXTRA

To the Heart of Peace Hoofprints

English Town's Role in Westerns

Horse Sense and Nonsense New Black Horse Westerns

More websites, more blogs. . .

. New forums have emerged lately willing to host a diversity of views on

western fiction. Sadly, the same diversity is not so easily found in the

book-publishing world. A respected Spur Awards winner confesses he no longer

enjoys reading "cookiecutter" traditional westerns while publishers' new releases

consist in large part of reprints of books from earlier decades. The "same

old, same old" continues to give critics of westerns the excuse to ridicule them.

Meanwhile, the Black Horse Western series, published in London by Robert

Hale Ltd since 1986, has been praised for a willingness to incorporate a

wide range of material. BHWs have to date not shied away from presenting

the work of the author who has a fresh angle on the expected staples;

is ready to stand out from the crowd with a little daring -- though never so

much as in Deadwood -- and is keen to satisfy the tastes of changing

times.

In this edition of the Extra, two BHW writers who have coincidentally

spent large parts of their working lives as journalists talk about their

methods and inspirations. Brian Parvin's first book for the line appeared

in 1992; Keith Chapman's, in 1993. Brian has three pen-names; Keith, one.

Brian has written continuously and has completed 48 westerns; Keith's total

is less than half that number. Other differences are almost as easy to

spot.

Keith's article, about the writing of a new Chap O'Keefe

book, Peace at Any Price, speaks about the creation of characters

who can be seen other than as "black" and "white" absolutes, and who undergo

life-changing experiences which he hopes will surprise and sometimes shock.

Not for him (or his readers) the comfortable predictabilities of the old-time,

Saturday matinée cowboy film.

The interview with Brian explains how he picks up on the mannerisms

of the people he meets in real life and uses them to help inspire his fictional

characters. But he also says his readers want a black and white story.

"The villain is very black. The hero is very white." And the outcome of his story is assured

from the start. The getting there is the major issue -- "the beauty of

it".

Keith placed some emphasis on historical setting and research when

writing his latest novel. Brian's readers don't want history, though he

knows he must be careful with the details of weaponry and clothing.

These writers each had two BHWs released this year that were

quickly declared out of stock ("no search results") at Hale's official

website. Keith's Misfit Lil Fights Back was history only

seventeen days after its publication date! Brian's Bluegrass Bounty

disappeared almost as quickly. Clearly, they are keeping the customers happy.

So it isn't a case of one has the wrong approach and the other the right

. . . just a couple of interesting case studies that prove a genre-fiction

line doesn't have to turn a writer into a hack working in the strait jacket

of a single, well-worn formula.

Also in this issue, we are joined by loyal BH Extra contributor Greg

Mitchell with another of his valuable backgrounders. This time it's not

on a gun, but on horses, ranches and cattle. And as always, the Hoofprints

section puts us on the track of those snippets of western news and information

that might otherwise be missed. Everyone's help is appreciated. Please

join in and send your views and news to feedback@blackhorsewesterns.com

|

|

|

Chap O'Keefe maps a BHW's trail

TO THE HEART OF PEACE

Jim Hunter and Matt

Harrison’s Double H ranch thrived . . . till their crew marched away to

war’s glory, and they were ruined by outlaws who burned them out and murdered

the last man on the payroll, harmless oldster Walt Burridge.

When the war ended, the two H’s started over. But for Jim war and the

Reconstruction had wrought changes beyond endurance. His former sweetheart,

pretty Alice Cornhill, had been claimed by another. So Jim rode out and

into the arms of his wartime love, the gun-running adventuress Lena-Marie

Baptiste.

There, he was quickly trapped by his vow to avenge Old Walt. How would

he choose between enmity and love, life and death?

Back cover

Peace at Any Price

THE die-hard followers of the western have had renewed cause lately to

shake their heads in bemusement. Once more the genre has come under

the scrutiny of the Hollywood herd. In particular, director James Mangold's

successful remake of the 1957 feature 3:10 to Yuma had

the movie pundits wondering whether the old shoot-'em-up still had some

life in it.

Could it really be the western hadn't been buried on Boot Hill years

ago?

For the greyer and more cynical, the debate had all the familiarity of

swirling gunsmoke in the last reel. The '80s and the '90s had Tinsel-town

western revivals, too. What the film-makers have tended to forget time

and again is that the traditional western staples are, by themselves, not

enough. Any successful movie has to come with a well-constructed, compelling

storyline, characters whose fates are involving, and a dash of originality.

One of the more perceptive commentators and reviewers it was a pleasure

to read was Bruce Westbrook. In the Houston Chronicle -- after making

the usual observation that Yuma was based on an Elmore

Leonard story -- he stated that the '57 screen version starring Glenn

Ford drew "clear inspiration from the lonely heroics of High

Noon earlier in that decade.

"What made that film a classic wasn't its violent confrontations but its

depth of character, and this new Yuma can make the

same claim," Westbrook said.

"Great western drama doesn't erupt from the barrel of a gun

so much as burn from the depths of a human heart."

|

|

David Whitehead

|

This is a message that the true aficionados have been trying to explain

to the critics and the genre's detractors for years. Here, at Black

Horse Extra, it has been stated by the writers, too -- in particular,

by David Whitehead.

David has said, "The single biggest development has been the awareness

of just how important character is in a story. In the early days, characters

were clear-cut -- with one or two exceptions -- and cardboard in the

extreme. But in the early 1950s a new breed of western writer came along,

and decided to mix a little of the good and the bad into their characters."

The novel Peace at Any Price, which I wrote in mid 2006,

gave me a special chance to explain what we meant, not by a further declaration

of the theory but by demonstration. As soon as the germ of the plot

had suggested itself, and a cast of principal characters was assembled,

I knew Peace

was going to be a book which afforded a better than average shot at crafting

a story which might help support the argument. I hope I haven't squandered

the chance and that the characters capture the interest and sympathy of today's

audience.

The beginnings were not auspicious. When the synopsis was submitted as

a proposal, publisher John Hale had only two comments, and the first

was reserved for the story's setting: "I would prefer the story to be

set entirely after the conclusion of the [Civil] War but perhaps this

is what you already intended."

Well, perhaps I didn't, but no writer of Black Horse Westerns lightly

ignores the preferences of a publisher who has been producing and selling

his line for more than twenty years. For most writers, the synopsis he

or she draws up in advance is seldom an exact outline of the finished

work, and I took heart from Mr Hale's closing remark which was, "Otherwise

I am sure the novel will be your usual splendidly professional and exciting

work."

|

|

|

When I'd written the book, I was able to tell Mr Hale that the War Between

the States features only briefly as a background for Chapter 2, The Breakup

-- less than a fifteenth of the finished work -- and as the background

for a brief, four-page flashback in Chapter 7, Betrayal Under the Stars.

But the war's impact is everywhere, and especially in the raw emotional

torment it brings to the characters' private lives.

Like Mr Hale, and possibly the library buyers on whose opinions he bases his

requirements, I prefer westerns not to have all-out battle scenes of

a strictly military nature. But I can recall, too, satisfactory westerns

where at least the first 20 pages (or reel) are quite thoroughly accounts

of war -- roar of cannon, men wounded and dying, others with swords,

bayonets and guns clashing on bloody fields.

The first chapter of Peace, Black Night on the Double H,

though set at the time of the war, is very traditionally "western". It

describes the destruction of Jim Hunter's and Matt Harrison's Texas cattle

ranch by rustling and arson, but it has no war action, just marginal

mentions of the historical facts. These establish the reasons the ranch

is short-handed and provide the first hints of the all-important catalyst

for Jim's and Matt's split, which is central to the plot.

|

|

|

For five years,

Jim had given the Double H some dash in its dealings with the world. He’d

choose the precarious trail over the safer if it promised more profit

or the spice of excitement. He was happy to leave it to his long-time friend

Matt to supply the partnership venture with stability and security. Truth

to tell, he was drawn by the Confederate cause.

|

|

|

To have set the story entirely after the war would have meant beginning

at Chapter 3, Return to Trinity Creek, and forgoing the chance of a hard-action

opening. This starting-point also would have entailed more than a few

explanatory flashbacks at some stage. In a book of BHW length, too much

backtracking is undesirable and likely confusing. Possibly it can involve

breaking the cardinal "show don't tell" rule as well. For me, a lengthy

report of key incidents delivered in the pluperfect tense as a kind of

synopsis within the body of the main narrative is never an appealing option.

Another solution to time-line problems, and one favoured from time to time by

Hale western writers, is the separate Prologue, but as a reader I find

this trick an uninviting way to open a short book. I want to be caught

up in the main story immediately.

Taken from the dates standpoint alone, the difference in where to begin

Peace was small. Was the start to be during the war,

in late 1863, or after it in April 1865? A choice was made for the former

and accepted.

Mr Hale's second comment was to me the more important, since its subject

was the characters whose hearts and loyalties were going to be tested

and thrown into turmoil by the war.

He said, "It is not particularly clear at the outset who is intended to

be the hero and, of course, an identifiable hero throughout is essential

. . . . Jim does not emerge as the classic hero. Perhaps this is something

you could bear in mind when writing the novel."

I believe I have, though Jim Hunter, like most heroes in O'Keefe books,

is not without flaws. In that sense he still isn't the classic hero.

Jim is "grey" not only in the Civil War context but in terms of a believable

spread of traits, good and bad. As noted previously, successful western

movie-makers and novelists, from Max Brand onward, have eschewed the old,

B-movie "black" and "white" stereotypes.

A novel today demands strong and interesting characters. Once they're

on the scene, it's strange if a plot doesn't grow naturally out of

conflicting personalities. In Peace, Jim, Matt and Alice

Cornhill and their powerful feelings form a tragic triangle. They came

alive of their own accord and it would have been hard to avoid the passion

and the drama springing from their situation.

|

|

|

She could see full

well why Jim was quitting the pain of shared life with his friends on

the Double H; to stay and possibly succumb to temptation would have been

treachery. And she understood all of this so well because her own heart

ached. The sun was rising but Alice felt like it was going down on her

world.

|

|

Candice Proctor

|

A few months ago, at Candy's Blog, writer Candice Proctor (aka C. S. Harris)

wrote about the dread with which many authors view the preparation of

a synopsis. Candy's advice was: "Lie." She told her readers, "Well, maybe

not lie, exactly. Just sort of bend and twist things so that they fit

into an exciting storyline that’s easy to follow despite the fact you’ve

left out suspects, characters, huge chunks of motivation, clues, etc,

etc. . . . Maybe some writers are such gifted synopses-crafters that they

don’t need to fudge a few details. But the fact is, if you’re writing a proposal

for a book that isn’t written yet, the finished product is probably going

to differ in significant ways from your outline anyway.

"So you’re not exactly being dishonest just because you don’t slavishly

follow an outline your editor is never going to see anyway. I’m not talking

about making major changes here. I’m talking about combining two minor characters

into one, or shifting sequences, or simplifying explanations – no more

than it takes to keep from tying yourself into knots and getting bogged

down in details. And who knows? In the process of telling your story in

synopsis form, you may actually find ways to improve your novel."

To this I responded, "A good synopsis on synopses! I say don't dread them,

use them. We had a similar debate here [Candy's excellent blog] when

you raised the question of the Plotter v. the Seat-of-Pantser [the writer

who embarks on a novel without pre-planning].

"Like yourself, I invariably depart from my synopsis in significant

ways, combining minor characters and shifting sequences. For example, in

Peace at Any Price, I decided the heroine's mother was best

dead before the story started, and that her space was better occupied by

a woman friend for the villain.

"And because the book is largely set in a small town on the Gulf

coast, a climax involving a fairly conventional gun duel was given a whole

new look by staging it amidst a hurricane. At the time I prepared the synopsis,

I hadn't even thought about Galveston 1900, so I can't say I deliberately

left that out, but it does illustrate how, with the basics safely taken care

of in the synopsis, you can concentrate on the improvements."

|

|

|

A bad night was

had. Not until early next morning did the fury of wind and water abate,

though the sea’s swells continued and the skies stayed cloudy. Fully two-thirds

of the town was gone. Corpses were washed up everywhere. . . .

|

|

|

Although the famous Galveston hurricane came 35 years after the time of

my story, research produced contemporary acounts that gave me a good picture of

the effects such a catastrophic event would have had on a coastal settlement

of the period.

By the book's end, I think I could fairly say the surviving characters

had undergone life-changing experiences. Much of vital importance had been

at stake for them, and I'd done my best to satisfy the follower of their

trials and shifting fortunes with a fitting outcome.

|

|

|

|

|

Seeing stars. Seeing stars.

|

A new set of western tracks

HOOFPRINTS

Ray Foster (aka Jack Giles) agrees with our panel (see September edition) that

books come with good covers and bad covers. "My weakness for covers has

more to do with the film images of James Coburn, Clint Eastwood et al -- like Michael Thomas's cover for Ride the Wild

Country which has Burt Lancaster in the closing scenes of the

film Lawman, done in reverse and without the wagon behind

him. Or a book called High Plains Vendetta [by Dale

Graham, 1994] which has a High Plains Drifter-style Clint Eastwood.

Those covers interest me. . . . I have

seen only one cover for a Hale western that struck me as John Turner-esque

and that's Leatherface [by Jack Giles]. As I like

Turner's paintings (which John Ruskin referred to), I liked that

cover. One that left me stunned was the cover to Poseidon Smith:

Vengeance Is Mine [also by Jack Giles]. I don't know the artist but I'm sure he never met my father, and that is who is on

that cover -- and he read more westerns than I could count. We were always

exchanging books." Ray says that after the cover, he looks at the blurb: "I

don't need too much information. So, having dispensed with covers

and blurbs, the books that I buy or borrow have to have grabbed me from

the first page. It's the writing that matters. If I judged a book by

its cover I would never have read Wilbur Smith's first novel; if I judged a book by its blurb then I wouldn't have read many authors at

all."

|

|

|

Missouri Secretary of State Robin Carnahan continues to

manage her family’s 900-acre farm and Angus cattle operation. She has also

helped modernize and strengthen Missouri’s public libraries through grants

to improve access to information using technology. A page at her SOS website

is headed "Western Fiction in a Series". It begins, "If you have ever

read a novel that you did not want to end, and you are a fan of westerns,

then this is the bibliography for you!" Nineteen authors are listed, ranging

from Zane Grey and Louis L'Amour to Richard S. Wheeler

and Elizabeth Fackler. Being an American library list, no BHW series

are included, alas. Interestingly, a sentence that appears no less than

eight times is, "Some strong language, violence, and explicit descriptions

of sex." Seems like the fanatically puritan have failed to impose their

repressive will on the libraries of Missouri!

|

SOS endorsement.

|

Publishing legend. Publishing legend.

|

Publisher Erastus Beadle (1821-1894) launched his Dime Novel series

in June 1860. During the Civil War, he sent his books to the front in

bushels, alongside food rations, introducing thousands of young men to

the pleasure of reading them. Like today's BHWs they were standardized

products, distinctively packaged and issued to a regular schedule. Dime

novels transformed the publishing industry. The Beadle company, though

much imitated, had published more than 7,000 of them by 1897. Total sales

in the first five years, to 1865, were nearly five million copies. Dime

westerns were also responsible for introducing what in more modern times

has been known as the "docudrama" -- mixing fact with fiction and sensationalizing,

for instance, episodes in the life of William Cody, who was made

famous as Buffalo Bill. Novels about the escapades of Jesse

and Frank James were eventually banned from distribution by the

Postmaster-General of the United States. The argument was that they turned

outlaws -- still living at the time and still dangerous -- into heroes.

|

|

|

Ready to take a joke? In a satirical article in the British Telegraph

newspaper, Craig Brown listed "14 Things You Didn't Know about the

Western". A couple of rib-tickling samples: "Between 1860 and 1890, baddies

in the Wild West were legally required to wear black hats, so that they could

be identified as they rode into town and shot on sight. Similarly, all ladies

working in bordellos were required to undertake regular medical check-ups

to ensure that they still had hearts of gold." And: " Russell Crowe's

new 3:10 to Yuma is, in fact, a remake of 4.50 from

Paddington. Crowe's role was taken in the original by the redoubtable

Dame Margaret Rutherford." Elsewhere in the Telegraph, Sheila

Johnston reported under the heading Letters from America: the Western

Revival: "Today the western is back in town, all guns blazing. Last year's

Brokeback Mountain, Tommy Lee Jones's Three Burials

and Australia's The Proposition were just the opening shots.

Liam Neeson and Pierce Brosnan saddled up last month for

Seraphim Falls; currently 3:10 to Yuma tops

the American box-office charts."

|

Pistol-packin' Margaret. Pistol-packin' Margaret.

|

Bob . . . multi-tasker.

|

Blazing into the global town that's the Internet came Saddlebums Western

Review, launched in late August by Gonzalo Baeza and Ben Boulden

after discussion at another blog. Ben said, "Saddlebums is the place

for news about the western genre." His premiere post attracted 35 welcoming

comments, including several from the BHW community, though an attempt to

unsaddle Saddlebums supporter Chap O'Keefe -- whom some have felt compelled to regard as a bête noire -- saw the near-anonymous

instigators fall on their faces. Ben concluded, "Chap is absolutely right

when he said 'This forum is for open discussion. It is not a behind-closed-doors

place. Nor, as far as I know, will anyone try to suppress you or your views

here.' Everyone is welcome, as well as their views and ideas." Only private grievances were ruled out. To continuing

acclaim, Ben and Gonzalo went on to review a fine range of books and to

interview top writers. The lineup included Brian Garfield,

Robert J. Randisi and Johnny D. Boggs. The versatile and prolific

Bob Randisi told Saddlebums, "I have a TV in my office, so I usually watch

while I’m working. Last week I watched all three Magnificent

movies on tape while I worked on a western. Also some old Warner Bros. westerns

like Cheyenne and Maverick. Then, while working

on a mystery, I’ll watch some Sunset Strip or Hawaiian

Eye tapes, maybe some British mysteries or movies, like Tinker,

Tailor, Soldier, Spy, or American films like Harper

or Chinatown."

|

|

|

Two mass-market Berkley paperbacks published by Penguin Group USA in

2001 and 2002 have been reissued as BHWs for the UK library market. They

are Winter Kill and Dead Man's Journey by Frank

Roderus. The author says he wrote his first story -- a western naturally!

-- when he was five and has never had any ambition since but to write for

a living. He has been producing fiction full-time since 1980 after a career

in newspaper reporting. As a journalist, he won the Colorado Press Association's

top award, for Best News Story, in 1980. The Western Writers of America

has twice named him a recipient of their prestigious Spur Award. In 1983

he won the Best Novel award with Leaving Kansas and in 1996

he won the Best Paperback Original award for Potter's Fields.

Frank is a lifetime member of the American Quarter Horse Association. He

now lives in Florida and, with his wife, Magdalena, plans to divide

his time between Florida and Palawan Island in the Sulu Sea.

|

Spur winner reissued. Spur winner reissued.

|

All-rounder's work.

All-rounder's work.

|

BHW author David Whitehead (aka Ben Bridges and Matt

Logan) was another pleased by the Extra's last edition. "I wasted little

time in getting to the latest BHE. Yet another triumph! Absolutely packed

with news and as usual quite beautifully presented. . . . The forum idea

[on book covers] worked well, and I found the article on artist Michael Thomas

of great interest. By coincidence, I'd just received a few copies of my

large-print Janet Whitehead romance A Time to Run from

Linford publishers F. A. Thorpe and was startled to find that he had painted

the illustration for that, too. . . . Thank you yet again for your sterling

efforts to promote our genre. It may be a cliché, but BHE really is

going from strength to strength, and I feel that this may be the

best issue yet."

|

|

|

As the western shot its way back on to the big screen this year, director

James Mangold told San Jose Mercury News correspondent Jeff Anderson

how he couldn't sell the idea of a 3:10 to Yuma remake to

any studio. "No one wants to make westerns. We got financed by a bank, and

they sold it to Lionsgate while we were in production," he said in San Francisco.

"I think the western has gotten really misunderstood lately. People view

them as kind of a period picture, or a historical picture. I think they're

a kind of a fever dream. They have as much in common with science fiction

as they do with The Age of Innocence." With the Yuma remake

a box-office hit, Mangold was confident the western could catch on again.

"As long as people like Johnny Cash were embraced, a western can be.

It's really about truth -- bare-bones truth." Mangold was

accompanied to 'Frisco by Peter Fonda, who plays bounty hunter Byron

McElroy in the movie about a rancher's attempt to bring an outlaw to

justice. Fonda said the western was "a wonderful way to tell stories about today. You're tricked

because you only see it afterwards. While you're watching, you're not thinking

about Iraq. This is what elevates it beyond other kinds of movies."

|

Studios' cold shoulder. Studios' cold shoulder.

|

Bid to be fresh. Bid to be fresh.

|

Multiple Spur Award-winning author Richard S. Wheeler voiced disenchantment

at the Saddlebums and Ed Gorman blogs. "I'm going to get myself into

serious trouble with western readers and confess that traditional westerns

have worn out their welcome in my reading pile," he said. "I love to write

them because I can attempt something novel and fresh; I don't love to read

them any more, and sometimes I simply hate the damned things." And: "I had

occasion recently to read a classic gunfighter novel by a very successful

western novelist. It carefully strung together every cliché of that sort of

story ever invented. . . I try not to write or read cookiecutter stories,

so they mystify me, along with those who read them." Meanwhile, a list of

westerns for October leaned heavily on reprints of classics by the likes of

Bret Harte, Clarence E. Mulford and Zane Grey. Except for BHWs, the smattering

of genuinely new entries consisted almost entirely of the latest titles in

anonymously written, house-bylined series.

|

|

|

BHWs' print-runs are calculated primarily to fill the requirements of

libraries in Britain and Commonwealth countries, many of which have standing

orders for new releases. Consequently, titles that prove popular also present

supply problems for the publisher and the distributors. Among the recent

books that have fallen into this class are the Misfit Lil stories.

The good news for readers who have enquired is that the first book in the

series, Misfit Lil Rides In, originally published in July

last year, is now available again everywhere -- US included -- in a large-print,

trade-paperback edition from Dales Westerns (Ulverscroft). The new book has

impressive cover art by Gordon Crabb. Gordon is one of the most highly

respected cover artists active in the UK today and has also worked consistently

for US publishers, including Bantam, Dell, Daw and Tor Books. Dales have

also just reissued the out-of-print BHW The

Lawman and the Songbird, featuring Joshua Dillard. Next year, among others, Dales has the

latest Dillard book lined up; Sons and Gunslicks appeared

as a BHW in March and was another title that quickly went out of

print at the publisher's. And a diary note for those determined not

to be disappointed is that the fourth Lil BHW, Misfit Lil Hides Out,

will be published by Hale next March.

|

Second chance. Second chance.

|

|

|

|

Shrewsbury

|

Brian Parvin's real-life sources for characters

ENGLISH TOWN'S ROLE IN WESTERNS

Dawn came up

that day in the town of Random on a bad note. They found a respected local

man dead, hanged by the neck from the tree in the livery corral. And things

were about to get worse with the discovery of the victims of murderous slaughter

and rape at a nearby homestead.

Were the two events linked? Was a bunch of crazed killers

on the rampage; a lone gunman hell-bent on some personal retribution? The

days that followed drifted from fear into nightmare as the town and its

folk fell prey to the torment of Edrow Scoone and his ruthless sidekicks.

But then a stranger, scarred and silent, booked himself

a room at the Golden Gaze saloon.

Back cover

Mist Rider

BLACK Horse Westerns are written by authors around the

world, including the United States, Australia and New Zealand, but with

the books published primarily for the UK library market, it's not surprising

the largest contingent is based in Britain.

Brian Parvin, who writes his

westerns as Dan Claymaker, Jack Reason and Luther Chance, hails from Shropshire,

a county in the west of the English Midlands, bordering on Wales. It is

fine pastoral country with hills and woodland, agriculture and dairying.

Brian -- and Dan, Jack and Luther -- live in its beautiful, medieval market

town, Shrewsbury.

Shrewsbury was listed as Brian's home in the old Hale print catalogues

which predated the helpful new company website. His first western, Rain

Guns by Dan Claymaker, was published in 1992. Before that, he had

written science fiction, fantasy and wildlife stories.

His 1986 novel The

Singing Tree was a post-holocaust animal fable about a quest by

a fox. It was described as "a dramatic story of love and survival that

celebrates the affinity between wildlife and humanity . . . and our future

together". Other similar novels under his own name were The Golden

Garden (about hedgehogs, 1987) and The Moon-Keepers

(about badgers, 1988). All were published by Hale.

|

|

|

Brian's work has also included mystery fiction and the following titles:

The Deadly Dyke (1979), Death in the Past (1980),

Dead Wood (1980), Then There Was Murder (1981),

Dawn Boys (1989) and Wreath for a Ragman (1999).

As the Hale company withdrew from some genres and expanded its BHW list,

the author switched to westerns and has now written 48. Despite his crime

fiction writings, Brian's westerns do not have any emphasis on mystery. His

books for the genre cannot be categorized as "crossover" novels. In August

he was interviewed by Tony Neal for his local newspaper, the Shropshire Star,

whom we thank for some absorbing insights to the writer's career and modus

operandi.

Brian believes, "The readers want a black and white story. The villain

is very black. The hero is very white. And good will undoubtedly triumph.

It has to. That’s the beauty of it as far as I’m concerned. It’s got

a great moral message. They know who is going to die within about four pages.

They know, probably within ten pages, who is going to do the killing.

It’s the getting there that’s the major thing. That’s the beauty of it.

How is the hero going to do it when the odds are stacked mercilessly against

him?"

Brian, a retired journalist, follows the old advice of drawing his fictional

characters from real life. He pays special attention to uncommon gestures

and mannersisms. To folk in the very English county town of Shrewsbury

it must have come as a surprise when the Star reported they could have

fictional counterparts striding the old American West!

|

|

|

It is not that Brian bases his heroes and villains on the people he meets

day to day, but like an old-time stamp collector perpetually adding new

specimens to fill blanks in his album, he seeks out and takes note of

the distinctive mannerisms, gestures and little traits that add up to make

a memorable individual.

"I don’t think anyone would obviously recognize themselves. But there are

certain characteristics. I don’t suppose they’re peculiar to Shrewsbury. You

could not take a whole person. You would never be able to interpret that person

because you would never get to their soul. What you can do is take a part,

a portion -- a mannerism is the word."

Brian seizes on a main characteristic and it becomes the vivid touch for

which he lets a principal in his story depend for realism. It's an old,

old trick to fix the character in the reader's mind. Done judiciously, it works.

One of his westerns pulled from the shelf at random illustrates the technique.

The Gun Master by Luther Chance is set in the small town of

Peppersville -- a much-modified Shrewsbury? -- which is awaiting attack by

the murderous Drayton Gang. The only top gun in town is a stranger called

McCreedy. We learn little about him and even at the book's end, he remains

largely a mystery without so much as a first name. This author, remember,

isn't out to challenge our grey cells.

|

|

|

What we are given to enjoy is a gallery of fearful

townsfolk, each defined by a key mannerism. Undertaker Ephraim Judd is

given to peering dolefully over his polished pince-nez. Storekeper Byron

Byam grips the lapels of his tailored frock coat. Preacher Peabody clears

his throat carefully but deliberately, or coughs, before speaking. And

so on. Members of the Drayton bunch, when they arrive, are given

to spitting -- a lot. (Spitting is a common habit in the West of Brian's books

but we're sure it's not on the streets of Shrewsbury!) Readers are reminded

about these things from time to time, and it keeps them clear about who's

who. They are not greatly distracted with characters' back stories, private

agendas or deeper motivations. Chapters are swift bites, mostly of six or seven pages.

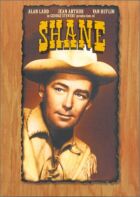

But paradoxically, Brian’s favourite movie is Shane -- the

classic, one-man-against-the-odds western in which characters are not

of the black-and-white variety and the story is emotionally and morally complex.

The old western movies clearly have a nostalgic appeal. Brian told the

Star, "When I first met my wife her passion was westerns. If we went to the

flicks, as they were known in those days, she would choose a western. I

thought, that’s something I have never done. Could I do it? Could I write

a western? And I did."

Today, his wife continues to play a vital support role in the production

of the Parvin westerns. He writes first drafts in longhand, and she types

them up. "It’s a partnership, a team effort," he said.

Brian maintained that he takes on a different identity for writing under

each of his pen-names. "Dan [Claymaker] is the thoughtful one. Jack [Reason]

is the man of action, for want of a cliché. Luther [Chance] has a slightly

humorous side. He sees the funny side of things. As my wife says, she has

been married to four men for a long time. She never knows quite who she

is waking up with."

|

|

|

What is not in doubt is the four's mutual approach to the western. Readers

and other authors have recently contended the western should be breaking

out of its narrow, classic form. They point out that for variety you don’t

need to go further than actual history and the numerous historical episodes

and characters that haven’t been dealt with so far in the fiction of the

West. But Brian had a warning about delving into parts of the West's rich

history that haven't been tapped:

"As a writer of westerns you have to be very careful. If you try to write

a history of the real West, then you are not appealing to your western

reader. He knows a fair bit about these frontiers, Indian wars, wagon trains,

and crossing the great plains, but he doesn’t really want to be told about

that."

For readers of the genre, there were certain expectations and conventions,

he said. It was a romanticized, fictionalized version of the American

West.

While readers didn’t want history, Brian could not be careless with the

details. "My readers will quickly pick up anything that’s loose in the

form of weaponry, such as a Colt or a Winchester repeating rifle. All

these things you have to be careful about. Similarly with clothing. Broad-brimmed

hats. Never say trousers -- always pants. And so on."

Unlike many of his writing colleagues, he is qualified to speak about

the use of guns in conflict, having served with the Gurkhas in Malaya.

He has vivid memories of some hard-kicking military firearms. "I can tell you one thing -- recoil is phenomenal."

|

|

|

What he has not done is visited the places that today occupy the mythical

territory of his books.

"I have travelled in many countries throughout the world, but have never

been to the American states. And sometimes I feel a little bit fearful

about doing it. If I went out there, I would certainly want to go right

into the Mid West, and I just wonder whether I would be a bit disillusioned.

Would Utah seem quite as Utah seems to be in my books?"

|

|

|

|

|

|

Greg Mitchell rounds up broncs, ranches and cattle

HORSE SENSE AND NONSENSE

The sheriff turned to

the middle-aged man riding beside him."Harry don't seem to be too worried."

Those were the last words that Henderson ever spoke.

King Leslie fired from concealment and put a rifle bullet between

his eyes. The posse was now in a trap and the outlaws closed it. Rapid, close-range

fire poured in from three sides. The surprise was complete and its effect

devastating. Men were smashed from saddles, horses reared over and fell backwards

or collapsed as though their legs had been swept from under them. A few fired

back at the puffs of gunsmoke spouting from among the rocks but most wheeled

their mounts and fled back the way they had come. The slaughter was unrelenting.

Some threw up their arms and fell from their mounts, others slipped off quietly

as though they had fallen asleep. Wounded men clung to saddle horns as they

fled with all thoughts of fighting gone. Now only survival counted.

Killer's Kingdom

Greg Mitchell

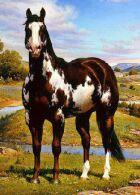

THE other night I was reading the comment about black horses (the real

ones) that headed the article "Judging Books by Their Covers" in the last

Black Horse Extra. I found myself agreeing. I've ridden a lot of black horses

at different times and have encountered some good ones but none that I would

call outstanding. They have to be taken as you find them.

In my younger days, when I was employed on the massive, unfenced cattle

properties of Australia's north, I always worked on the assumption that

a good horse was never a bad colour, but was wary of piebalds and skewbalds

(paints, pintos etc.) mainly because the two best riding breeds, the Arab

and the Thoroughbred, do not have these colours.

Broken colours indicate inferior breeding, and breeding is important

in terms of a horse's weight-carrying ability and endurance. A well-bred,

medium-sized horse can carry weight better than a coarsely bred animal that

may be half-draught. and a couple of hundred pounds heavier. Though it's

not my favourite color, the really outstanding horses I've had have all

been bays.

The wandering cowboy of fiction seems to be able to carry all he needs

on his riding horse. In reality, not much can be packed on a saddle even

with a pair of large saddlebags. A single blanket takes up a lot of room

and the bedrolls carried by cowboys in cold country were far too large

to carry on riding saddles. Coffee pots and frying pans are particularly

awkward. The real howler, still appearing in books, is when the hero cooks

himself bacon and eggs for breakfast. Eggs are not designed for carrying

on horseback.

It would be possible to travel from town to town and stay overnight

in hotels, but that would also be expensive. A man could spend a night

out in the open with just what he could carry on his saddle though it

would not be a comfortable night, especially in cold or wet weather. When

travelling where towns were more than a day's ride apart, most westerners

would use either a horse or a mule as a pack animal. From an author's

point of view the presence of pack animals can hamper a character's movement

so it makes sense to leave them out, but the real wandering cowboy would

use them.

|

Paint

Paint

Mustangs

Mustangs

|

|

A lawman, a farmer, or someone based in town might ride the same

horse all the time but cowhands on big ranches and trail drivers changed

their mounts daily.

Mustangs

were plentiful and cheap but many were too light for roping. Likewise,

they were too light for cavalry use as the average cavalry load of 240

pounds was out of proportion to their bodyweight (700-900 pounds). Their

light weight also worked against them when roping heavy cattle. Indians

got good mileage from mustangs because they carried little on them and changed

them often.

Quarter horses had the weight averaging around 1,175 pounds

and had plenty of short-distance speed. On rough ground, where they could

not use their long, low stride, other horses were just as fast and some

had more endurance.

Draught horses were unsuitable mounts for big men. Draughts

have too much of their own weight to carry, are rough to ride, can be

clumsy and lack stamina at faster paces. With body weights from 1,600 pounds

to more than 3,000 pounds, their different bone structure makes them unsuitable

for riding.

Arab horses were good but were not common in the Old West. Though

usually bigger than mustangs, 15 hands is fairly big for an Arab horse.

Weight can be 900-1,000 pounds.

Morgan horses weighed slightly over 1,000 pounds and were

riding or light harness types. Despite what is often written, they were

not used to pull heavy wagons. Some were used in light harness for buckboards

or buggies but they lacked the size for heavy draught work.

|

Quarter horse

Draught horse

|

|

Thoroughbreds were the favoured mounts of many army officers and

proved their ability on a great number of nineteenth-century battlefields.

The breed should not be judged by the broken-down fugitives from race tracks

that today give such an unfavourable impression of these horses. No other

breed of horse can carry even the light racing weights at the same speed

or over the same distances. With an average height of about 16 hands and

mostly weighing between 1,050 and 1,200 pounds, they had the size to make

them good weight carriers. Thoroughbreds of good conformation, properly

acclimatized to the country, are very good workers indeed.

Stallions are often selected as mounts for fictional heroes,

but they are a bad choice to ride. They will fight other horses if there

are mares about and if they are near a mare in season they are prone to

forget what their riders want. A stallion hitched to a rail in a town

would cause no end of trouble and would be most unlikely to wait patiently

at the hitching rail while his master disposed of the villains. The army

never used stallions except on breeding establishments.

|

Morgan horse

|

|

The outlaw King

Lesley set up his kingdom in the San Christobal

Mountains. From there, he plundered the countryside around Henly Springs for

two years. Finally the townspeople pressured their local sheriff into leading

a posse against the outlaws. But they were ambushed by Lesley's men and a

massacre ensued. Was salvation at hand when Marshal Rod Delroy arrived in

town with the mission of rescuing any survivors? The issue was complicated

by the intervention of Mort Wolfe, a man driven by his desire for revenge

against Lesley. Rod faced many dangers before the outlaw threat could be removed.

Back cover, Killer's Kingdom

|

|

|

Ranches and cattle

Large ranches would never have had an accurate count of the number of

cattle they had on the open range. They were mixed in with other brands

until roundups in spring and autumn, where calves were branded and stock

selected for sale. Local ranches were all represented at roundups. There

was little point in rustlers running off herds of branded stock. They

would be hard to hide and difficult to sell unless brands were somehow

altered. Cattle were earmarked as well, and an earmark was often harder to change

than a brand. Most rustlers concentrated on stealing unbranded calves.

In the years following the Civil War it might have been possible to sell

stolen, branded cattle, but the ranchers soon devised means of dealing with

the problem with properly registered brands and earmarks. Altered brands

could be seen on the flesh side of the skin when the animal was killed.

Night watches were kept only on trail herds. Ranch cattle were not

coralled every night, so when rustlers struck it was often difficult to

know how many head were missing. Successful rustlers usually needed a

few days' start if they hoped to escape with a large number of stolen cattle.

Cattle tracks are almost impossible to hide and splattered manure as opposed

to one neat pile advertises to all that animals are being driven.. The often-described

trick of concealing tracks in streams would not work very well as it

would be hard to hold a large number of cattle in a stream and they would

make very slow progress. Vengeful ranchers would see where the herd went

into the water and it would not be difficult to find where they came out

again.

Most ranchers preferred the open-range system because they could run

far more cattle than their relatively small ranches could carry. One

cattle baron with hundreds of thousands of cattle actually owned only

18 acres of land. But when it suited their purposes, the ranchers would

use barbed wire as readily as the small homesteaders. Not all of the latter

were hard-working, god-fearing folks and some would often claim virtually

worthless land at strategic places to gain control of vital water or to

extract tolls from the big Texas herds moving north. This practice contributed

greatly to the demise of the traditional cattle trails. Conversely, the

big ranchers were too quick to brand honest homesteaders as rustlers.

There were good and bad on both sides.

|

|

|

Despite the paranoia about sheep, and what is often claimed, sheep and

cattle can graze on the same pastures. In many countries of the world,

they do. Sheep, however, can eat lower than cattle and an area over-grazed

by sheep can be badly damaged. The most important part is to avoid over-grazing

by either species. Under the open range system, sheep were shepherded continuously

while cattle were left to fend for themselves. If sheep ate all the feed

in one area, it meant that the cattle had to travel further afield for grass

and walked condition off themselves in the process. It also made them harder

to find at roundup time. In the sheep or cattle controversy, neither side

showed any great desire to compromise. The ranchers had the men and guns

and it suited them to vilify sheepmen to force them off the range. The sheepmen,

in turn, could destroy large areas of land if they held their flocks too

long in the one place -- and they did have a tendency to do this.

-- Paddy Gallagher, aka Greg Mitchell, whose

next BHW will be Range Rustlers.

|

|

|

|

|

|

NEW

BLACK HORSE

WESTERN NOVELS

Published by Robert Hale Ltd, London

978

| Peace at Any Price

|

Chap O'Keefe

|

0 7090 8269 9

|

Running Crooked

|

Corba Sunman

|

0

7090 8415 0

|

Dead Man's Journey

|

Frank Roderus

|

0

7090 8431 0

|

| Killer's Kingdom

|

Greg Mitchell |

0

7090 8459 4

|

Redemption in Inferno

|

H. H. Cody

|

0

7090 8488 4

|

The Bounty Killers

|

Owen G. Irons

|

0

7090 8489 1

|

Manhunt in Quemado

|

Daniel Rockfern

|

0

7090 7686 5

|

Desolation Pass

|

Lance Howard

|

0

7090 8328 3

|

Hammer of God

|

P. McCormac

|

0

7090 8490 7

|

The Bull Chop

|

Abe Dancer

|

0

7090 8492 1

|

Wilde Country

|

Tyler Hatch

|

0

7090 8499 0

|

Judge Parker's Lawmen

|

Elliot Conway

|

0

7090 8500 3 |

Guns Along the Gila

|

Walt Masterson

|

0

7090 8478 5

|

Gold for Durango

|

Carlton Youngblood

|

0

7090 8501 0

|

Tough Justice

|

Skeeter Dodds

|

0

7090 8502 7

|

Dead Man Walking

|

Ethan Flag

|

0

7090 8509 6

|

Mistake in Claymore Ridge

|

Bill Williams

|

0

7090 8504 1

|

Last Stage to Lonesome

|

Scott Connor

|

0

7090 8510 2

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Black

Horse Westerns can be requested at public libraries, ordered at bookstores,

and bought online through the publisher's website, www.halebooks.com, or retailers including Amazon, Blackwells,

WH Smith and VinersUK Books.

Trade inquiries

to: Combined Book Services,

Units I/K, Paddock Wood Distribution

Centre,

Paddock Wood, Tonbridge, Kent TN12 6UU.

Tel: (+44) 01892 837 171 Fax: (+44)

01892 837 272

Email: orders@combook.co.uk

For Australian Trade Sales, contact DLS Distribution Services, tradesales@dlsbooks.com

For Australian & New Zealand Library Sales, contact DLS Library Services, swalters@dlsbooks.com

DLS Australia Pty Ltd, 12 Phoenix Court, Braeside, 3195, Australia.

Ph: (+61) 3 9587 5044 Fax: (+61) 3 9587 5088

|

|

|

|

|

|