|

|

Authors of westerns tend to be shadowy figures, often cloaked by the anonymity

of multiple pen-names or names owned by publishing companies. Many show little

interest in the books beyond writing their own. Fortunately for western

readers and publishers, notable exceptions occur. One of them was Geoff

(Jeff) Sadler -- novelist, genre historian and defender of the BHW's reputation.

Geoff's spur has rung its knell, far too prematurely, at age 62. In this

issue of BHE, another writer motivated by sheer generosity to the genre,

David Whitehead, pays tribute to his old friend. He also recalls for us

in a second contribution how Geoff went up against those who tried to debunk

the western in a notorious British TV show called Burning

Books.

Further on, we present another cluster of Hoofprints for the keen western

trackers' eyes, some amusing, some informative, and a mini-autobiography

from a BHW writer whose early western ventures included a George G. Gilman

fanzine and who is now involved in the British crimewriting scene.

To wrap up, we have a reality check. In Writers and Money (always a hot

topic!), an active BHW contributor reveals some of the quirks in the unnatural

justice that determines who gets what and why in 2006.

|

|

|

A tribute by David Whitehead

TYING UP AFTER A GREAT

RIDE

The run-up to Christmas 2005

was overshadowed by news of the death of BHW writer Geoff Sadler, who

passed away on 6 December.

Geoffrey Willis Sadler was

born on 7 October, 1943 in Mansfield Woodhouse, Nottinghamshire. He started

work as a library assistant in 1960, and married Jennifer Watkinson five

years later. Always a western buff, he would later cite the likes of Les

Savage Jr, Jack Borg, Louis L’Amour and Matt Chisholm as major influences

-- and certainly Geoff’s own westerns were always marked by a strong sense

of the visual, accurate gun detail and believable characters who were

not easily forgotten.

The majority of Geoff’s westerns

chronicled the adventures of a half-Apache, half-Scottish lawman named

Andrew Anderson, a character who bears more than a passing resemblance to

the character played by John Wayne in Hondo (1953) -- a film,

incidentally, which also had quite an impact on the author. The books were

usually set against a backdrop of deserts and dust, of glaring heat and

sudden, often brutal violence, but there could be lighter moments, too,

as in the Canada-based Headed North (1990), where the character

of “Byron W. Holmes” was clearly based upon the author’s good friend and

fellow BHW writer, B. J. Holmes.

Geoff created Anderson when he was about twelve or thirteen, originally

recording the half-breed marshal’s fast-paced exploits in longhand. One

of these early efforts, Kingdom of the Desert (in which a

stranger cleans up a corrupt town and tames the four-man syndicate who run

things for their own ends), later formed the basis of his first published

book, Arizona Blood-Trail (1981).

Geoff followed this with

Sonora Lode (1982), an intriguing book in which the action

is virtually confined to a doctor’s surgery and an undertaker’s parlour,

symbolically representing the two basics of life and death. This gun-running

story also introduced the sinister, amber-eyed Amarillo -- an enemy with

whom Anderson would lock horns time and again.

Not that Geoff limited himself

to the western genre. In 1982, he penned a trilogy of “slaver” novels

which were published in paperback by New English Library. These “Justus”

books -- The Lash, Bloodwater and Black

Vengeance, are well worth seeking out, and show beyond all doubt

that Geoff was a writer of considerable range and skill.

Geoff’s third Anderson book,

Tamaulipas Guns (1982), meanwhile, remains one of his best,

offering as it does a strong, original plot that is told with great pace,

and laced with a whole catalogue of unforeseen twists. And there were more

impressive plots to come; in Severo Siege (1983) the town

for which Anderson acts as marshal comes into conflict with a die-hard Confederate

determined to create a new “Trans-Continental United States.” Sierra

Showdown (1983) pits Anderson against a gang of ageing Mexican

War veterans who return to the area to reclaim a long-buried stash of stolen

gold bars. The courtroom drama Throw of a Rope (1984) finds

Anderson accused of murder, and facing the very real prospect of death by

hanging. And in Saltillo Road (1987), the US Government sends

Anderson to the steamy swamps of Louisiana to break a smuggling operation.

In the late 1980s, Geoff

adopted a second pseudonym, “Wes Calhoun”, and created the character of

Chulo Pritchard, a mild-mannered black ex-Army scout who would sooner avoid

trouble than have to deal with it. Chulo came about when Geoff was researching

one of the Anderson books, and chanced upon a photograph of an amiable-looking,

slightly overweight Negro cowhand. However, Chulo only ever appeared in

a handful of adventures, including Chulo (1988), At Muerto

Springs (1989) and Texas Nighthawks (1990), and never

really enjoyed the lasting popularity of Anderson.

In any case, Geoff was asked to edit the second edition of Twentieth

Century Western Writers at around this time, and went on to make

a magnificent job of the assignment, creating a book that remains invaluable,

even fifteen years on. Mike Linaker, Mike Stotter and I were among the

contributors, and I know I speak for all of us when I say that Geoff was

an absolute joy to work with -- calm, methodical, supportive and always

good-humoured. Phone calls from Geoff were never fraught or filled with

complaint. What I remember most are all those cheeky wisecracks and all

that wicked laughter.

In later years, this father

of two sons fought a brave battle against motor neurone disease, but still

managed to turn out the odd local-history book, learned critical essay

or BHW here and there. Sadly, however, the fight ended on 6 December, 2005,

at which time we lost not only a fine writer, but also a most articulate

and charismatic spokesman for our genre.

Geoff was an intelligent,

caring author whose plots reward careful study. He once told me, “My books

are intended as entertainment … But it is to be hoped that it is entertainment

with a little added depth, some hint of authenticity, and some moral conflict.

I’ve never sat down and thought, Right, now I’ll take the Western from

shoot-’em-up to Art. But if the story gets to the audience, it has

to satisfy me first of all, and to do that it has to contain some

deeper quality, some strength that makes it worthwhile. In that respect,

I suppose, it does go beyond pure entertainment."

I can only recommend that, if you haven’t already done so, you check

out Geoff’s western legacy, and see for yourself. I'm quietly confident

that you won’t be disappointed.

-- David Whitehead (aka Ben Bridges and Glenn Lockwood), whose informative

new website is at www.benbridges.co.uk.

|

|

|

Geoff Sadler's battle

with the intelligentsia

SHOWDOWN ON CHANNEL FOUR

When St James Press published

the second edition of Twentieth Century Western Writers in

1991, editor Geoff Sadler was invited to discuss the western genre on Burning

Books, a highbrow TV show which was broadcast on a then-minority

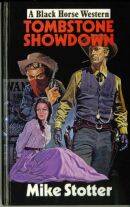

British television station called Channel Four. Mike Stotter’s BHW Tombstone

Showdown and my own book Law of the Gun by David Whitehead

were also included in the discussion, which aired on 10 November, 1991.

From the outset, however, the

producers displayed a shameless but wholly predictable anti-western bias.

They couldn’t have been more disparaging if they’d tried. The opening voice-over

dismissed the books under discussion as “pulp” westerns -- “the final

frontier of popular fiction, where cardboard cowboys save the West from

the savage Indian.” Though quite obviously hardbacks, Mike’s book and mine

were both described as paperbacks, and when Geoff Sadler finally

appeared on screen, the caption which appeared beneath his image misspelled

his surname.

Joining Geoff in the debate

were architectural lecturer Joe Hagan and writer Julie Wheelwright, neither

of whom was even remotely qualified to discuss the subject with any degree

of authority. Indeed, they were both of the opinion that western fiction

was all about a “masculinity thing”, with Hagan further suggesting that

the writers of such books were “just knocking them out for the money”.

Geoff, of course, disagreed.

“They write them because they like doing it,” he countered in his

wonderfully gentle Nottinghamshire accent. “They identify with the characters--

”

But that was as far as he got,

because at that point, Wheelwright leapt in with: “But isn’t there something

problematic in identifying with these gunslingers?”

Now, this was and remains an

argument which has always mystified me. I mean, I can see where it might

be “problematic” to identify with the villain of the piece. But

to identify with the hero, who usually represents honesty, integrity, determination,

loyalty and courage, who treats the fairer sex with respect and admiration

… call me old-fashioned, but where’s the “problem” with that?

Joe Hagan then singled out Law

of the Gun for a few misguided observations. In the final shootout,

my heroes, Sam Judge and Matt Dury (referred to by Hagan as “these two blokes”)

find themselves fighting for their lives against some pretty riled-up Apaches.

Vastly out-numbered and in a kill-or-be-killed situation, all they can do

is quite literally fight for their lives. And yet Hagan described them as

“slaughtering” the Indians “indiscriminately”. And so I was accused of racism.

When Wheelwright proposed that

the western was “a dying genre … on its last legs,” Geoff again disagreed.

“It’s a minority genre,” he corrected her. “But it will continue.”

Knowing Geoff as well as I did,

I had not the slightest shred of doubt that he argued his case articulately

and coherently throughout the recording, and yet he was given only minimal

airtime in the final programme -- certainly nowhere near as much as Messrs

Hagan and Wheelwright. And even though he observed that the western enjoyed

“a hard core of popularity”, the narrator of the show still wrote off our

BHWs as “the last gasp of a dying genre”.

I rang Geoff after the show

ended. He was philosophical about its harsh treatment of the western, and

I suppose that he -- we -- could hardly be anything else. But BHW

writer B. J. Holmes was so angry that he complained about it in the pages

of his local paper. In a letter headlined “NOT READY FOR BOOT HILL YET”,

he wrote, “Anybody interested in the western (either as a reader or a writer)

will be painfully familiar with outsiders who have an out-dated mental stereotype

of what they think a western is, which they then proceed to criticise.

[Burning Books] was no exception, allowing two outsiders

to air their misinformed views.”

Still, we have always toiled

in a much-maligned, minority genre. To the uninitiated -- BJ's infamous "outsiders"

-- ours is a world of “Cowboys and Indians”, “This town ain’t big enough

for both of us”, “White man speak with fork tongue” and other assorted clichés.

Or is it?

Because as I sit here, writing

this, I’ve just realised that it is now more than fourteen years and three

days since that programme was broadcast. And where is the western, that

“dying genre” that was “on its last legs”, now?

It’s still standing, my friends.

And standing taller than ever.

When my first BHW was published

back in 1986, John Hale used to issue six new westerns each month. Now he

issues ten new westerns each month. Large print editions are everywhere,

and in more demand than ever. The BHW site attracts new members on an encouragingly

regular basis. And Mike Linaker reports that western sales in the United

States are on the increase.

All of which goes to show that,

in its prejudiced examination of the western, Burning Books got

everything wrong. And what it identified as “the last gasp” of the genre

was actually the genre simply getting its second wind. Because we’re still

here. We’re still writing. And we’re still being read.

Geoff was right. The genre did

continue. I wonder whatever became of its detractors.

-- David Whitehead

|

Hagan: "Slaughtering.

. ."

Wheelwright:

"Last legs."

Holmes:

Holmes:

"Outsiders."

|

The Grey wolf.

Out of ideas.

Dead man's tales.

Dead man's tales.

Narrow

views.

Narrow

views.

Mystery ingredient.

Mystery ingredient.

|

Our column of lighter impressions

HOOFPRINTS

The private lives of most BHW authors are closed books to their

readers, but maybe it was always so. Only now are the facts emerging about

Zane Grey (1875-1939), the archetype of the manly, outdoors adventurer

and writer. His escapist novels, mostly westerns, have sometimes been declared

flawed by their "pompous moralizing against sin". But in a new biography,

Zane Grey: His Life, His Adventures, His Women (University

of Illinois), Thomas H. Pauly tells that Grey was arrested at age

16 in a brothel and that there exists "an enormous, totally unknown cache

of photographs taken by Grey of nude women" throughout his life. In many

of the pictures, Grey is there, too, naked and engaged in sex. Pauly says

the writer's long-suffering wife, Lina Elise "Dolly" Grey, knew

of his affairs. "How could she not? Many were with relatives of hers or

women she knew. At first hurt by them, she later came to regard them as

part of her husband's makeup that would never change" Her summing-up of

her husband's personality was: "The man has always lived in a land of

make-believe, and has clothed all his own affairs in the shining garment

of romance. . . ."

Mike

Linaker (aka BHWs' Neil Hunter and Richard Wyler)

misses no chance for a change of writing scene, writing Gold Eagle

paperback epics for Canadian-based Worldwide. With three months to

go to the deadline for an action-adventure novel of 95,000-100,000

words, Mike told Hoofprints, "I'm getting into the new book now. I've some mileage

to make up, and it's really going to be hands on. I've been doing research

on Iran, Jordan, the Bedouin tribesmen and their customs, language.

If writing for Gold Eagle does nothing else, it certainly gives me

an insight into different cultures. Who says writing isn't educational!

Last year it was China, before that Russia, and the last one was

set in the Colorado Rockies, with a smattering of Bosnia. . . ."

We hope his imagination and the publishers will soon be luring Mike

back to the Old West!

A group of A-list filmmakers — Clint Eastwood,

Quentin Tarantino, Taylor Hackford, Paul Schrader, Peter Bogdanovich

and Robert Towne — commented on the career and influence of

a talented B-movie director in a TCM documentary, Budd Boetticher:

A Man Can Do That. USA Today said Eastwood and Boetticher shared

at least one important trait: a love of the western. But speculating

on what the paper called the genre's overall decline, Eastwood said,

"People just aren't writing that many good western stories. A lot of

[the ideas] have been exhausted.When I did Unforgiven

in 1992, it was a wonderful script. I thought, 'This would be a perfect

last western for me.' " Writers be warned -- be sure to add original

elements to your next story of a lone rider's revenge or feuding cattlemen

and nesters. Otherwise the Man With No Name isn't going to be interested!

The British Telegraph newspaper sent travel writer

Simon Horsford to Monument Valley on

the border between Arizona and Utah, the location for many famous

western movies and a favourite with director John Ford. Horsford

found John Wayne's legacy everywhere. In the restaurant, they

served "Wayne's favourite meal" of fried chicken, mash and gravy.

In the nearby store, they had John Wayne Toilet Tissue. "Fortunately,

eating one does not necessitate the use of the other," Horsford said.

"In fact, the chicken supper was quite delicious -- even if it was washed

down with a bottle of non-alcoholic beer." Seems you can't walk into

the bar and demand a shot of rye either -- there is no bar since the area

is "dry".

Bioanthropolgist Jerry Conlogue, of Quinnipiac

University in Connecticut, told Discovery News about analysis of a

mummy nicknamed Sylvester who was a 19th century cowboy. Since

shotgun pellets blasted Sylvester's right cheek years before his death

and he appeared to have survived a bullet to his collarbone, the "wild"

in Wild West was confirmed. But his liver was in good condition -- so

not all cowboys drank as hard as they lived. The mummy was

owned by a California doctor whose uncle was one of two cowboys who found

Sylvester’s body in 1895 in the Gila Bend Desert. It was preserved with

arsenic and probably went on the sideshow circuit as an "outlaw mummy".

Conlogue's magnetic resonance and computerized tomography images showed

no arthritis or degenerative disease. Teeth indicated an age between

35 and 40. "In Sylvester's chest, both lungs appear to adhere to the front

of the chest wall. This may be an indication of some infective process

in his respiratory system." Andy James, of Ye Olde Curiosity Shop,

Seattle, where Sylvester is displayed, was surprised. "My great grandfather

started this store in 1899. I was led to believe a gunshot wound killed

Sylvester. . . a bullet fragment entered his abdomen, bounced off a bone

into his lungs and caused him to bleed to death."

Australian BHW writer Keith Hetherington liked the Chap O'Keefe

article in BHE about Indians and their harsh treatment, War Paths and Peace

Pipes. "Fascinating. As O'Keefe suggests, it's a bad mix really -- good guys

and bad guys on both sides. I've only ever met two Red Indians -- and they

were nearly black! It was at a place called Redcliffe near Brisbane when

I was kid during the [Second World] War. My father got talking to them. They

were with a Yankee outfit stationed at Toorbul Point just up the coast and

used to hit Redcliffe in the old landing barges for R & R. Met my first

Mexican there, too, but all he could do was finger his gold crucifix and

say his mother must be worrying about him. . . ." The hardworking author's

latest book is Madigan's Mistake, issued under one of his four BHW pen-names, Hank J. Kirby.

Clerkenwell House has been known for decades as the headquarters

of BHW publishers Robert Hale Ltd. But it seems London EC1 has had

another Clerkenwell House foisted upon it -- a skinny, steel-and-glass

erection not so much added to the city skyline as squeezed into a slot

between two existing buildings. Why use the same name? We don't know, but

the award-winning architect of the newer, just 11-feet-wide Clerkenwell

House is Joe Hagan -- believed to be the same who is introduced by

David Whitehead elsewhere in this issue of BHE as a misguided critic

of the Hale westerns on a TV show called Burning Books. Maybe

authors should be doubly careful to include the "45-47 Clerkenwell Green"

line when addressing their packages to the proper Clerkenwell House. What

happens to misdelivered western manuscripts is a burning question we haven't

pursued. . . .

James Mangold, director of the Johnny Cash biopic Walk

the Line, will remake the classic, 1957 western movie 3:10

to Yuma, which was based on a suspenseful Elmore Leonard

story. Mangold has looked over the yarn and found subtleties overlooked

fifty years ago. He told showbiz paper Variety: "There are a lot of good-bad

themes that were only touched on in the original. A lot of westerns are

meditative, but this is a total struggle culminating in a showdown, which

has the potential to be one of the great movie gunfights." The old B&W

movie, directed by Delmer Daves, has been described by fans as "a

distinguished psychological drama", and was largely played out in the claustrophobic

setting of a hotel with the key players under mental and physical siege.

The poor, family-man rancher (Van

Heflin) and the bold, womanizing outlaw (Glenn Ford) each

wanted what the other didn't have.

The latest Chap O'Keefe BHW, available from UK online retailers

and on request at public libraries, is Ghost Town Belles.

O'Keefe tells us, "The scariest content in this tale isn't a conventional

spook but the conduct of the belles' father, Mad Dungaree Dan. And the book's

most conspicuous feature from a writing point of view is that it gives

bigger play to a trademark feature I've inserted in every O'Keefe BHW from

the first, Gunsmoke Night. It's rather like the cameo appearance

by himself that director Alfred Hitchcock used to wangle into every

movie, but it isn't myself in disguise. Nor, indeed, a character at all. Just

an item that will always be there to a greater or lesser extent in each book.

In Ghost Town Belles it's prominent and it's woven significantly

into the storyline." No prize to the reader who can tell us what it is! No

prize, that is, beyond the author's congratulations and his gratitude for

keen reader support.

You're based in Bury St. Edmunds, England, it's March, you're writing

your BHW -- and you want to know what time the sun goes down in Tucson,

Arizona, in June. What do you do without leaving your keyboard? Try www.timeanddate.com/worldclock/aboutastronomy.html

. Tip: use Full List

rather than Standard, so you can pick Tucson from a wider range of world

cities. When you get to your city, click on the line that says Find sunrise

and sunset times for other dates.

|

On

far-flung horizons.

Dry

valley.

Dry

valley.

No R & R for Hank.

Classic revisited.

Classic revisited.

|

|

Crime scene editor Mike Stotter looks back

THE WESTERN AND I

Whenever I'm tempted to look back over my life

and simply take stock -- which isn't very often, I have to say -- the one

thing that always surprises me is just how big a part the western has played

in it. I didn't write my first BHW until 1989, when I was thirty-two, but

the genre and I -- correction, the genre, BHWs' Dave Whitehead and I -- go

back much further than that.

I was born in the East End of London in 1957. Dave was born in the same area

almost exactly one year later (we actually missed sharing the same birthday

by just three days). We were introduced to each other at primary school by

a mutual friend when I was nine and he was eight, but it wasn't exactly love

at first sight. In fact, we didn't really have much to do with each other

until we met up again some years later, at secondary school. This time, something

-- I don't know what it was -- just clicked,,, and a firm friendship was born.

Because all this happened long before the days of PlayStation and X-Box,

we always made our own entertainment. Movie-mad as we were, we used to choreograph

stunt-fights at our local park -- always saloon brawls, naturally -- and

spared no effort in trying to really "sell" every punch and kick.

In our quieter moments we wrote and drew our own comics, usually stealing

ideas from the likes of Marvel and DC. But even here, the western played

its part. Dave used to write and draw an outlaw character called "The Scarlet

Bandit", while I chronicled the adventures of Wyatt Earp. Inspired by the

Larry and Stretch books of Marshall Grover (which were then to be found in

just about every newsagent's and market bookstall), we also co-wrote a series

of stories about two cowboys-turned-detectives called Henry and James. Since

"Henry" is Dave's middle name, and "James" is mine, you can see that we didn't

exactly believe in stretching ourselves creatively at that point!

Dave's Dad -- who had always dreamed of what life might be like as a movie

mogul -- bought a Standard 8mm cine camera in 1969, and the three of us soon

set about making a movie. It was -- surprise, surprise -- a western called

The Fast Gun. There wasn't much of a plot as I recall,

but I do remember that I played the bad guy and Dave (with those matinee

idol looks of his) played the goodie. It only ran for five shaky and often

out of focus minutes, but we had a really good time making it, so over the

next fifteen years we made about thirty five more. They weren't all westerns,

of course, but a fair number were. I even got to play the hero in one of

them!

When the Edge westerns of George G Gilman first hit the stands, we quickly

became avid fans. In fact, as far as we were concerned, ol' "Triple G" couldn't

write them fast enough for us. Eventually, Dave decided to start a fan club

for the man himself, and with the blessing of the author -- alias Terry Harknett

-- and Edge publisher New English Library, ttthat's exactly what he did. I

helped out wherever and whenever I could.

It was a great collaborative effort. But in 1977, Dave's father (who had

always been such a tremendous help behind the scenes) died suddenly, and

I think it's fair to say that Dave's heart just wasn't in it after that.

So we agreed between us that I would take over the club, and somewhere along

the line Steele Edge, as the club magazine was called, evolved into The Westerner,

which more accurately reflected the input of such other British western writers

as Laurence James, Angus Wells, Mike Linaker and Peter Watts, as well as

cover artists like Tony Masero and Dave McAllister.

It was Angus Wells who first suggested that we attempt to sell the idea of

a western magazine to a professional publisher, and in 1979 we did just that.

No one was more surprised than us when, amid much fanfare, TV and newspaper

advertising, etc., IPC Magazines launched Western Magazine in October 1980.

They did a fabulous job on it too, and kept Dave and I on as consultants

for the entire run. But only four issues were published before an unforeseen

journalists' strike put the kibosh on the project, and Western Magazine was

cancelled under the old "last in, first out" rule.

This, of course, was the height of the British paperback western, when the

so-called "Picadilly Cowboys" ruled the range. Dave had always wanted to

join them, and in 1984 he had his first western accepted for publication

by Robert Hale Limited. Incidentally, his pseudonym "Ben Bridges" is actually

the name of my nephew. Dave liked the sound of it and "borrowed" it.

Anyway, one evening we were chatting away, when Dave suddenly suggested that

I write a BHW of my own. I'd always fancied having a go, of course, but never

actually did anything about it until then. So I wrote McKinney's Revenge, which was accepted and published about a year later. Ol' Thad McKinney returned in McKinney's Law

three years later, and in between times I also created two other continuing

characters, Jim Brandon and Joshua Slate, who have so far galloped through

two BHWs, Tombstone Showdown (1991) and Tucson Justice (1994). As Jim A. Nelson I wrote Death in the Canyon in 1997.

These days, a full-time job in the City of London, and my duties as editor

of crime fiction website Shots ( www.shotsmag.co.uk), keep me fully occupied.

I still manage to write a fair amount of factual material (including the

award-winning children's non-fiction title The Best Ever Book of the West

in 1997 and, more recently How Ancient Americans Lived), as well as short

fiction for American anthologies, but I still retain a particular affection

for the humble BHW, and hope to contribute some more westerns to the line

very soon.

For sure, Thadius McKinney is still lurking around in my PC somewhere, as is the beginning of his third adventure, McKinney's Rangers,

just waiting for him to power into action. Small wonder, then, that I have

such tremendous regard for the western genre -- it has played such a large

part in my life to date, and I have so many great memories associated with

it.

-- Mike Stotter

|

|

|

Getting to the nitty-gritty with Chap O'Keefe

WRITERS AND MONEY

For most of us, the compulsion to write fiction is accompanied by a need

for it to pay, or at least cover its costs. Otherwise, it has the makings

of an expensive hobby, eating up other income and time, and possibly health.

In the bygone days of pulps, fiction weeklies and even newspapers that ran

short stories, a correspondence school could advertise writing courses with

claims like, "There's gold in Fleet Street, but you have to dig for it .

. . These gentlemen say they can't get enough of the kind of stories they

need. . . . They'll pay you well and, when half Fleet Street is eating out

of your hand, your ego will expand like a sunflower. So will your bank acccount."

The Fleet Street referred to, hub of the British newspaper and magazine scene,

is no more. Elsewhere, the pulps are similarly long gone. Writing tuition

isn't offered under catch-cries as promising as "Make your ability pay" or

"Unlimited opportunities." So what are the potential rewards for the novice

writer today?

Let me begin chasing the money rainbow with a digression that has relevance which will become apparent later.

Author Mike Linaker (BHWs' Richard Wyler and Neil Hunter) is, in his own

words, a total film nut. One of his recent treats, aside from acquiring the

classic movie Stagecoach as a bargain DVD, was receiving among the Christmas

presents the Lord of the Rings trilogy, also on DVD.

He emailed me, "Last night I settled down to watch and just couldn't stop.

Apart from the fascination of the stories, I was so taken by the natural

beauty of the New Zealand settings. I hadn't realized just how beautiful

it was. Those fantastic views of green valleys with rising mountains in the

backgound. To say the least, I am really envious. I thought American landscapes

were great, but those NZ views are just breathtaking. It is fantastic . .

. This is where a large, widescreeen TV comes into its own!You are one lucky

feller living there."

I decided Mike was largely right.What I see from most of the windows of my

hillside home, including those of the room where I write, is what you see

here.

It's not LOTR, but it's pleasant enough and a distraction for which I ought

to be grateful. One of the attractions of New Zealand for the film industry

is the variety of landscapes it offers, from sweeping sub-tropical beaches

to lakes and mountains, glaciers and fjords. You can also turn bits of Wellington

and Lower Hutt into King Kong's New York! (And the art deco theatre in KK

is not a set, but an Auckland cinema, the Civic.)

About ten years ago, a film-maker appoached me with a proposal to do a screen

version of my BHW The Outlaw and the Lady. It was to be shot in NZ's South

Island with the Southern Alps doubling for the Colorado Rockies. Sadly, like

many movie-making propositions, it never got further off the ground than

an inch or so -- the thickness of the screenplay.

Today I live in what really has become a city suburb, but I still have intact

the impressive, 180-degree view across a creek estuary and the upper harbour

to the wooded peninsula of Greenhithe. The big white building behind the

moored yachts is a boatbuilder's premises and part of Hobsonville. The world

has recently seen Hobsonville, a former aerodrome, as a chunk of Narnia.

Also, I understand the low blue structure, which appeared around the time

The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe was shot, had something to do with that

movie. The range of hills in the background is the Waitakeres -- Xena and

Hercules land of TV fame.

So -- upshot of digression -- the writer who can live here has it made, right?

Well, no, he doesn't . . . and especially not a writer of library fiction

of the BHW type.

As most people who visit this site know, BHWs are not a trail to fame and

fortune. Because the books are issued as handsome but expensive hardcovers,

their buyers are almost entirely libraries. The books are marketed by imprint

and are often bought under standing order arrangements with no preferences

for particular authors specified, although the range of writing styles and

approaches is wide. Softcover reprints are large-print editions, again aimed

at the library trade.

Consequently, royalty income, as covered by the contracts for the books,

is seldom received by the author beyond the publisher's initial advance,

made against royalties in anticipation never realized. The author's money

fails to appear not because his or her book isn't read, but because every

copy is read by a hundred or more people who don't have to make an individual

purchase incorporating a fresh royalty payment.

The world is slowly coming to recognize the unfairness of the situation.

Enlightened countries have introduced schemes, usually under the label of

"Public Lending Right", or PLR, to compensate authors for their loss.

Britain, where most BHWs circulate, has PLR. I'm informed that a hardworking

BHW author with a backlist of fifty titles can earn £5,000 in PLR a

year -- that is, £100 of income every January for every book that's

in the libraries and being borrowed. This exceeds what the most productive

BHW writer can hope to earn from his publishers in one year, although I've

seen other writers dismissing PLR payments as "soup kitchen stuff". So over

a period of years, a reasonable return can be achieved, perhaps explaining

why many UK authors of BHWs have little motivation to spend time and effort

on promoting their work to potential retail buyers. The key objective is

to write as many books as quickly as possible and hope the distributors and

library supply companies will get them on to library shelves.

Though none of the rewards are huge, the principal paymaster for the serious

BHW writer living in Britain is not the publisher but the public purse --

a shadowy entity it would be impossible directly to address or sway through

promotion.

A writer who produced a handful of BHWs years ago told me privately this

year, "Just had my PLR in and happy to see old [hero's name from early '90s]

still drawing in the crowds."

A prolific writer who is one of the line's most respected contributors, and

who is based in another country which has a PLR scheme, told me a day later,

"PLR is a lifesaver for me." Converted to British pounds for the sake of

consistency, he was receiving £3,800, which far outstripped what even

he could earn in publisher's advances. What he deplored was that the payments

would cease when he died, and his heirs and dependants wouldn't be able to

continue claiming the earnings from his lifetime of effort.

"Doesn't seem to make sense to me: I mean, someone invents/manufactures a

car part, say, or a filter for a washing machine -- he can die the next day

after it's on the market and royalties keep rolling in to immediate relatives

and anyone else thereafter they wish to leave their rights to."

He also regretted that he couldn't claim the income from his many, many books

in the UK libraries. "I don't qualify for the UK PLR either, though I tried."

Here he struck to the heart of the PLR problem: The money is payable to writers

only on the basis of their being a resident of the country/political union

that has the scheme in place.

The BHW writer who lives in Germany, France or a raft of other European countries

is able to claim British PLR because of the European Union treaty.

But not the writer who lives in the United States or Australia . . . or New

Zealand.

One non-UK-based BHW stalwart contended that this amounted to discrimination

on grounds of residency in an age when discrimination on just about any other

grounds -- gender, skin colour, religious belief -- was outlawed internationally.

A British-based colleague responded, "It is an odd view as it'd never occur

to me that the Australian or Canadian governments should send me money because

my books are in their libraries. But I'll admit that if Scotland ever gets

independence from England, I'll be first in line to start complaining when

my English PLR dries up! I guess it's my prudent and pedantic accounting

training that makes me smile everytime I hear soundbites like 'PLR paid for

my holiday.' On one level that's right, but the accountant in me tells me

that it ignores the opportunity cost of the time spent to earn that cheque."

Agreed, PLR may never produce proper recompense for the hundreds of hours

of effort the best writers put into their work. But the response did not

address the point that something is better than nothing in the view of those

unfortunates receiving the latter while making an identical expenditure of

time and energy.

Nor did the same writer's revelation that only 7% of authors earn more than

£1,000 from PLR comfort the overseas authors. It did, after all, merely

reflect the well-known fact that a huge percentage of "authors" embark upon

their literary career to write only one or two books before abandoning it

for other pursuits. This applies both generally and to BHWs.

"Well, why be greedy?" I hear it asked. "Surely you just claim PLR in the country where you do live."

Alas, this is no answer for American BHW writers because the US has no scheme.

So Maine resident Lance Howard, with a couple of dozen popular westerns circulating

in Britain, unfairly receives nothing for their reading beyond the modest

initial payment. Nor is it a satisfactory answer for any Australian BHW writer,

because many more copies of his BHW books will be in British libraries than

in Australian.

And for a New Zealand writer of genre fiction, the suggestion is even less

help. His government's Authors' Fund scheme is very similar to Australia's

PLR, setting a qualifying minimum of fifty copies of a particular title to

be held in the libraries before a small payment is made. The difference,

however, is Australia has a population of twenty million -- five times

New Zealand's -- and probably more holding of library books in the same proportion.

The NZ scheme allows no compounding of holdings. Thus you could have forty-nine

copies of ten separate novels in the libraries (that is, 490 books being

read "for free") and receive nothing. Have fifty-one copies of one book and

you would collect a small payment.

These rules work against the writer of genre novels. When it comes to light

fiction, the NZ libraries are confronted with a wide choice and obviously

cannot afford to buy each and every title offered in a particular category,

like western, romance or crime. On the other hand, an even remotely popular

author has to fill an international publisher's/readers' demand for regular

new titles -- perhaps three a year under each pen-name -- thus diluting his/her

chances of having a qualifying book under the scheme. The libraries make

a selection, and if each of around seventy library buyers chooses a different

title from an individual author's list, he/she cannot hope to secure any

compensation.

I'm told one very successful, NZ-based Harlequin Mills & Boon romance

writer never bothers to register her books with the scheme. (It involves

registration of titles, making a statutory declaration before a Justice of

the Peace, and annual re-registration.) She relies for income solely on paperback

sales to the general public. Books read by library borrowers are regarded

as a financial write-off. They might help introduce new readers, who it's

hoped will then go to a store and buy the royalty-producing paperbacks --

an argument which doesn't apply in the case of library-only westerns.

Plainly, it's not a sensible financial choice for a BHW writer to live, as

I do, in a country like New Zealand which has only a fifteenth of the UK's

population or a fifth of Australia's. Too few books in too few libraries

paying too little money to the writers who qualify!

My advice to a BHW writer, current or aspiring, is to live in a well-developed,

wealthy, heavily populated nation that looks after its authors with a decent

PLR scheme. You'll need to be hardworking and patient, but you have the prospect

of eventual reward for your efforts.

Meanwhile, the NZ writer must make do with being a "lucky feller" and enjoying

the scenery. And enjoying his writing, of course . . . when he can afford

it.

-- Keith Chapman, who has written BHWs since 1992 as Chap O'Keefe. His latest book is Ghost Town Belles.

|

|

|

NEW BLACK HORSE WESTERN NOVELS

(Published by Robert Hale Ltd, London)

Ghost Town Belles

|

Chap

O'Keefe

|

0 7090 7841 2

|

Steel Tracks - Iron Men

|

Corba Sunman

|

0 7090 7892 7

|

Gambler's Dawn

|

Dale Graham

|

0 7090 7896 X

|

The Drifter's Revenge

|

Owen G. Irons

|

0 7090 7904 4

|

Hell in the Zunis

|

Clay Burnham

|

0 7090 7938 9

|

The Long Search

|

Alan Irwin

|

0 7090 7948 6

|

Guns on the Wahoo

|

George

J. Prescott

|

0 7090 7959 1

|

Hellfire

|

Scott Connor

|

0 7090 7960 5

|

Ponderfoot's Dollars

|

Ben Coady

|

0 7090 7961 3

|

Miller's Ride

|

Caleb Rand

|

0 7090 7962 1

|

|

|

|