|

June-August 2007

|

BLACK

HORSE EXTRA

David Whitehead's Fifty Notches Hoofprints

A Primer in Realistic Ballistics

Let's Do the Twist! New Black Horse Westerns

A sentence in our top feature below notes that Black Horse Extra has gone from strength

to strength. This is in the sense that the March edition attracted more

visitors than any before it. At the two-month point in its term, the edition

had received more hits than each of its predecessors over a full three months.

The improving results since the venture was launched are due to the effort

and support of a small, dedicated group. Our core interest is the Black

Horse Western novels published by Robert Hale Ltd, of London. These books

are written by a team of perhaps two dozen freelance writers. An accurate

tally isn't easy because of a tendency for the writers to come and go and

for some to work under several different pen-names simultaneously. Of the

active writers, only a minority are known to bother with spreading via the

Net the message about the continuing availability of what is broadly known

as the traditional western.

Everyone associated with Black Horse Extra would welcome participation

by their silent colleagues . . . their revelations, their fresh ideas, their

news. And readers' views are equally important to us. You can reach us without

obligation and promptly at feedback@blackhorsewesterns.com

Elsewhere, debate continues about the state of the western genre and the

need for it to be saved. In particular, US editor and book packager Russell Davis has been

making a commendable effort at his new blog Westerns for Today, with tentative

suggestions for a publishing venture and an education drive, plus an appeal

for more email activity, websites and blogs. It's a cause already dear to

hearts at Black Horse Extra and we hope to be able to lend a voice to Russell's

campaign. A good starting point is encouraging wider interest in the ten

new Black Horse Westerns published every month.

The gather on this range today includes an interview with genre stalwart

David Whitehead, a follow-up on western weaponry by Greg Mitchell, whose

article on the Walker Colt last time produced a unanimously complimentary

response, and the always popular gallop that produces Hoofprints.

Happy reading!

|

|

|

The Extra interviews 'Ben Bridges'

DAVID WHITEHEAD'S FIFTY NOTCHES

Knowing that if George wasn’t already dead, he very soon would be, O’Brien

turned his attention back to Pistol-Whipper, expecting -- hoping -- to see

the man turning tail and lighting a shuck.

Instead, he found himself staring right down the barrel of his

opponent’s Cavalry Colt.

He thought, Damn!, which was pretty mild considering

that he’d just used up his fifth and final shot on George, and the Lightning

in his fist was now empty.

Hard on the heels of that, he thought about the Winchester .45/.60

in the scabbard under his right leg, although he knew he’d never be able

to draw, aim, lever and fire the rifle before Pistol-Whipper blew him out

of this life and into the next.

All of which left him with only one other weapon to which he

had immediate access -- a weapon he used without further ado.

He bawled, “Yee-haah!” again, and the blood-bay beneath

him powered forward into a flat-out gallop, all thousand pounds-plus of

it headed straight for his adversary.

Draw

Down the Lightning

Ben Bridges

PEOPLE on the western fiction scene are far more familiar with David

Whitehead talking about other writers' work than his own. David has been

promoting the genre, championing the genre and recording the genre's history

for -- gasp! -- more than 25 years.

To general applause, David has been a real friend of Black Horse Extra

from its outset, contributing several major articles. This has been more

important than can be imagined by those not in a position to know what

goes on behind the scenes. At a pre-existing Net forum, a couple of BHW

authors, who shall remain nameless, had the odd notion that anyone expressing

views not suiting themselves or their friends should be denied an audience and fellowship. "I will not allow

any emails regarding another version of [BH newsletter] to be passed through

this group," said the man in charge. "Anyone doing so will be automatically

removed."

|

|

|

For a writer of David's stature -- among others -- the attempted ostracizing

cut no ice, and the Extra has gone from strength to strength, enabled to

do so with thanks from the books' publishers and by the unselfish donation

of authoritative material like David's fine features on Lauran Paine and

Marshall Grover.

The occasion of the publication of David Whitehead's fiftieth book -- a list that began with The Silver Trail in 1986 -- was

scarcely needed to prod us into turning the tables and demanding an interview.

BHE: First, congratulations on notching up fifty books! That’s

quite an accomplishment.

DW: Well, not if you compare me to the likes of Lauran Paine

or Geoffrey John Barratt, but I know what you mean, and I have to confess

that reaching this milestone has given me a great sense of achievement.

|

|

J. T. Edson

|

BHE: What can you tell us about your new book -- your first

in something like five years?

DW: Draw Down the Lightning is my fourteenth

Carter O’Brien yarn and I think it recreates the spirit of the earlier

O’Brien stories pretty well, in that he gets hired to solve or otherwise

deal with a seemingly insoluble problem and somehow, against all the odds,

manages to work everything out. The idea came from a TV show I happened

to chance upon one afternoon about fifteen years ago. It was all about

adopted children trying to find their birth parents. That in itself didn’t

provide the plot, though -- it was the occupation of one of the missing

fathers that really got me thinking. I won’t say too much, because I don’t

want to spoil the surprise, but it does go to show just where ideas can

come from.

BHE: Over the last few years you’ve become a regular commentator

on the western genre. Is it fair to say that you’ve always been a western

fan?

DW: Very much so. I was first introduced to the genre by

my father, who was a big western fan himself, so I was more or less born

all fired-up by the enormity of the land, the fortitude and optimism of

the pioneers, the code of honour the good guys were supposed to stick to

and the neighbourliness of those folks whose only hope for survival was

to stick together. I started reading westerns when I was about nine or

ten years old, beginning with J. T. Edson and Marshall Grover, both of

whom I eventually got to know pretty well. I started writing my own westerns

around the same time -- my first continuing character was “Clint Jones,

Railroad Detective”.

BHE: It has been reported that you wrote about twenty books

before you scored your first acceptance back in 1986.

|

|

Peter Watts

|

DW: That’s right. In 1974, at the tender age of sixteen,

I decided to stop writing just for my own amusement and to start producing

books of a more publishable standard. I wrote horror novels, westerns,

romances, non-fiction, all sorts, but all I got back from publishers was

rejection slips. I even embarked upon a massive project called Who’s

Who in Western Fiction, which I never did complete. Eventually I

decided to give it all up as a bad job, but then I injured my back, and

whilst recovering decided to dust off an old manuscript and revise it according

to comments and suggestions I had received from Peter Watts, better-known

as Matt Chisholm and Cy James. London publisher John Hale, of Robert Hale

Ltd, liked the end result and said that if I could cut out about 40 pages,

he would consider it “sympathetically”. I did, he did, and the rest is

history!

|

|

Terry Harknett

|

BHE: And along the way, of course, you started the Edge fan

club.

DW: Yes, that was in 1976. And I must say, the great privilege

and absolute pleasure of meeting Edge books author Terry Harknett turned

out to be one of those life-changing moments for me, because as soon as

I discovered that Terry wasn’t just George G. Gilman, but also Charles

R. Pike, William M. James, Joseph Hedges and Lord knows who else, I realized

that this was what I wanted to do as well -- to write westerns and masquerade

as different people.

BHE: How do you go about writing a book?

DW: For me, a new book always begins with one basic, I hope

“different” idea. The idea has to be new and original, otherwise it’s hard

to get excited about it. I want to appeal to both the traditional and

modern western reader, but not give him that dreaded sense of déjà vu

where he thinks, "Here we go again. Another range war. Another band of

renegade Indians. Another outlaw gang trying to recover lost loot."

Once I have the idea, it’s just a matter of getting it all down

in roughly the right order, throwing in a few set-pieces, some surprises

and an interesting supporting cast. All this may sound rather clinical,

of course, but it's just the planning. If there is any “art” involved, that

comes with the writing, of maintaining an original, interesting style that

keeps the reader turning the pages, of solving any problems the plot may

throw up along the way, of keeping things moving at just the right pace,

of building the characters layer by layer and finally tying the whole thing

up neatly within the required length. I haven’t always succeeded, but I

do care very deeply about the story and the characters, and would rather

have my teeth drawn than insult the reader by producing a second-rate piece

of work.

|

|

|

Ideas -- as you know -- come from anywhere and everywhere.

Squaw Man owes everything to one throw-away sentence I

read elsewhere. Coffin Creek had its beginnings in one boring

Saturday afternoon when I sat down and watched a kung fu movie called The

New One-Armed Swordsman. The Spurlock Gun was a westernized

retelling of an earlier, unpublished action-adventure novel I wrote called

City Combat.

BHE: What do you see as the major themes of the western?

DW: That good can triumph over evil. That with enough courage,

determination and grit, mankind can overcome any obstacle. That sometimes

a man or woman has no choice but to make a stand, and that by making

that stand they can actually change things for the better. Essentially,

the western is and always will be a morality play. We read them to affirm

to ourselves the validity of these ethics.

|

|

|

BHE: Clearly, you believe that the western has endless possibilities

and permutations.

DW: Without doubt. If you are creatively minded, and you

really care about your chosen genre, you can sit down and dream up a new

slant on practically any theme. All it takes is time and a little serious

thinking. But you’ve got to really want to create something original

to begin with.

BHE: Who are your favourite writers?

DW: It’s difficult to pick favourites. Some writers I enjoy

more than others, but overall what appeals to me is the basic sincerity

that every western writer brings to his work, that very genuine desire to

tell a good story the best way he or she knows how. I don’t get that feeling

with any other genre. There’s definitely something sincere about western

writers that I really like.

BHE: Then why do you think the genre is often maligned?

DW: If we’re going to be really honest about it, there have

been an awful lot of lousy westerns written over the years, so you can’t

blame readers for turning their attention elsewhere. In the past, characters

have remained one-dimensional or stereotypical, or the writers themselves

have continued to give the reader violence when what he really wants

is action.

BHE: What would you say have been the most important advances

in western fiction?

DW: The single biggest development has been the awareness

of just how important character is in a story. In the early days, characters

were clear-cut -- with one or two exceptions -- and cardboard in the

extreme. But in the early 1950s a new breed of western writer came along,

and decided to mix a little of the good and the bad into their characters.

Suddenly, the hero didn’t have all the answers. He was frequently as troubled

and uncertain as the folks he set out to help. The villains, too, have

undergone a positive metamorphosis. They have become villainous for a

reason -- a less-than-perfect upbringing, maybe, or a catastrophic experience

which soured them to life and what life had to offer. They became victims

of fate -- they all became victims of fate. And that has made the whole

genre much more interesting.

|

|

|

BHE: So what do you think makes a good western?

DW: Above all, a good western should make the reader share

all the emotions of the hero, with whom he or she instinctively identifies,

anyway. You want to make the reader feel the heat of the desert, the chill

of a mountain pass in winter, the smell of pine needles, the cool freshness

of the water in a secluded stream. You want to make him feel everything

the hero feels -- pain, joy, love, hate, even the savage satisfaction,

or stomach-turning revulsion, of finally settling things with the bad guy.

Make them feel exhausted, saddle-sore or determined. In short, you have

to make the experience as real for the reader as you can, write with authority,

and make sure they keep turning the pages.

BHE: After fifty books, do you still have plenty to say?

DW: I wouldn’t really claim to have anything to say, as such.

I have no message, no agenda, no ego. I see myself simply as an entertainer.

When you sit down with one of my books, my job is simply to entertain you.

If, along the way, I can also enlighten you, educate you, fascinate you

or fire you up, well, that’s a bonus! But I wouldn't kid myself on that

any of my books are particularly "important" in that way. Their job is solely

to help you forget about your lousy job, your demanding partner, your unpayable

mortgage.

BHE: What do you have lined up for the future?

|

|

|

DW: By a twist of fate, my 51st book, a romance called Winterhaven,

came out two months before my 50th. Three other romances as by "Janet

Whitehead" are all backed up and awaiting reissue in large print. I’ve

just completed a new script for the Commando war comic series,

which brings my total up to around thirty or so. And I’m writing a new

BHW called All Guns Blazing, which is a collaboration with

the German western writer Alfred Wallon. My next solo BHW will be Send

for Morgan Starr which I’m really looking forward to. I’ve been

plotting this one for a while now, and I think it’s going to be a good

one.

BHE: I’m sure it will, David! Thank you.

|

|

|

|

|

Bryson's reality.

Bryson's reality.

|

A set of fresh impressions

HOOFPRINTS

In Made in America, US-born, English-resident writer Bill

Bryson described the history of the English language in the United

States and the evolution of American culture. Naturally, he had a word

or two for the western. The genre's classic writers included Zane Grey, a dentist from New York City, who

knew about as much of the Old West as the average "city slicker" would, and Clarence

J. Mulford, who created in Hopalong Cassidy a cowpoke as fictional

as any has been. Neither author let ignorance of the subject matter stop him telling a

captivatingly romantic and, more essentially, saleable story. Real cowboys

mostly had boring lives that consisted largely of driving cows across

lonely, near endless American plains. Bryson said, "They certainly

didn't spend a lot of time shooting each other. In the ten years that

Dodge City was the biggest, rowdiest cow town in the world, only thirty-four

people were buried in the infamous Boot Hill Cemetery. Incidents like

the shootout at the OK Corral or the murder of Wild Bill Hickok

became famous by dint of their being so unusual."

|

|

|

Between 1887 and 1900, Karl Friedrich May (1842-1912),

fifth of fourteen offspring of an impoverished Saxony weaver, and a former

convict, wrote more than twenty adventure novels set in the American West,

including Winnetou and Old Surehand, giving

rise to the claim that the western was a German creation. May worked with

the aid of encyclopaedias, atlases, ethnological studies -- and an inexhaustible

imagination. He didn't visit the US till 1908 and didn't go farther west

than Buffalo, New York. Between 1912 and 1968, German film makers produced

23 movies based on his novels. In 13 of them, American actor Lex Barker

starred, sometimes as Old Shatterhand, "strong as a bear and invincible".

Three movies cast Briton Stewart Granger in the lead as Old Surehand.

Every summer, thousands of Karl May admirers attend an open-air Karl May

Festival in Bad Segeberg, Schleswig-Holstein, which has been held since

1952. Though largely unknown in the US, May has fans around the world, including

China, Japan, and Indonesia where a Karl May Society has its own website.

|

Father of western?

|

Joe the cynic.

|

Terry Harknett (aka George G. Gilman,

author of the famous 1970s Edge series) told his Piccadilly

Cowboys forum, "The book I am currently reading is The Devil’s

Guide to Hollywood by Joe Eszterhas, probably the most

successful screenwriter in the world. He is a bit of a cynic but I think

he tells it as it is for most of the time, based upon his experience of

movie work. Relevant to members of this message board is the following snippet

from his book: ‘ Don’t write a western. The odds are overwhelming that it

won’t be made and that if it is it will fail. Almost every year or so

there is a failed attempt to do a western – some, like Larry Kasdan’s

Wyatt Earp, have been especially good, but the public doesn’t

seem interested. A producer said to me, "A western in space, yes, a hip-hop

western, yes, but a western with horses, absolutely not."’ Depressing,

isn’t it," Terry said, "coming from the man who wrote Basic Instinct,

Jagged Edge, Flashdance and Showgirls

amongst others and so obviously knows of what he speaks."

But Eszterhas's reputation meant less than nothing to Terry's fellow Piccadilly

Cowboy Mike Linaker, aka BHWs' John C. Danner, Richard Wyler

and Neil Hunter: "There are screenwriters out there who could

outshine Eszterhas with their eyes shut."

|

|

|

Chap O'Keefe describes his BHW heroine Misfit Lil

as dark-haired and grey-eyed. Reader Jo Neville, of Torquay,

England, comments that this is a fairly unusual combination. By way

of response, O'Keefe supplies a quote from Carl W. Breihan's

book Great Gunfighters of the West, in which the young Bat

Masterson is described thus: "Bat looked as harum-scarum as he behaved.

He had a mop of black hair with oddly contrasting light grey eyes that

danced with devilry and merriment. He was of medium height, slender but

wiry, strong, and resilient. In store clothes and with his hair slicked

down, he was described as one of the handsomest men on the frontier. But

it was his slate-grey eyes that attracted attention. Gunfighters came in

all shapes, sizes and temperaments, but almost invariably they had blue

eyes." Misfit Lil's unusual eyes will sparkle next in Misfit Lil Fights

Back, out in July. For new readers, more about Lil can be found in

our Backtrails article "The Images of Inspiration" (BHE September edition).

|

To Bat for Lil.

To Bat for Lil.

|

From tall ships to tall tales.

From tall ships to tall tales.

|

Award-winning maritime-history writer Joan Druett tells us, "I

love westerns, a heritage of putting myself through university by ushering

at a B-grade movie theatre in Palmerston North, New Zealand. . . . I enjoyed

[the March] Black Horse Extra very much, especially the dissertation on the Colt.

I have to research arms occasionally, and used to drive to the Waiouru

Army Museum where there was a helpful sergeant. Once, I had to research

the Henry rifle, and the sergeant told a peculiar story about Abraham

Lincoln visiting both the Henry and Winchester workshops, and choosing

the Winchester for the Union army. Henry went bankrupt and killed himself.

The sergeant went on thoughtfully to say the ironic part of the tale was

that Lincoln was assassinated with a Henry rifle, not a pistol as the pictures

show. I think he was having me on." Our expert, Paddy Gallagher (aka

BHWs' Greg Mitchell) agrees. "Lincoln could not have visited the

Winchester and Henry factories. The first Winchester came out in 1866,

long after he was dead, when Oliver Winchester bought the Henry

company and improved on the Henry to make it the first Winchester. Lincoln

was shot with a Deringer, single-shot, muzzle-loading pistol. Later, when

variations of these weapons were made by a variety of companies, they

were called 'derringers' with an extra 'r'. The Winchester was never adopted

by the American army although some officers asked for them after General

Custer's defeat in 1876."

|

|

|

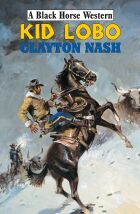

Keith Hetherington (aka Clayton Nash) tells Hoofprints he

had some doubts about his new book, Kid Lobo, in which

the hero, the best horsebreaker in West Texas, sets out to find the father

he never knew, the man who had run out on his mother, leaving her to work

herself to death in her efforts to raise him. Says the cover blurb, "He

wanted only one thing now: to find that man -- and kill him." Keith

says, "I wondered about this particular yarn, whether it would appeal

to publisher John Hale or not." But Mr Hale wrote, "I enjoyed Kid

Lobo, which is very tough stuff indeed. It all makes for a splendid

story which I am delighted to accept." Keith says he "allowed the characters

to kind of dictate what should happen next. It worked really well. I rarely

feel satisfied with my stories but this one seemed to hit the spot." We're

sure the book will be much enjoyed by BHW readers everywhere.

|

Splendid cover, too.

Splendid cover, too.

|

Homeric Jimmy.

Homeric Jimmy.

|

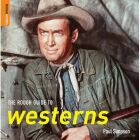

From the 1920s to the 1950s, the Hollywood studio system transformed

the violent, unruly facts of frontier adventurism into a body of myth, legend

and "moral clarity" to edify the most patriotic of Americans. But western

movies have been made all over the world. Everywhere, in fact, from China

and India to Russia and Czechoslovakia. In his recent book, The Rough Guide

to Westerns, entertainment writer Paul Simpson gives the reason as the universal

allure of sweeping historical sagas. Italian director Sergio Leone considered

western characters to be latter-day avatars of the ancient Homeric heroes,

and Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges praised westerns for keeping epic

forms alive in the modern era. Simpson's style is informal and his verdicts

sometimes surprising in a generously illustrated and hugely wide-ranging

book. As a DVD-top companion, the work should please movie buffs and western

fans alike.

|

|

|

A title should be vivid and have rhythm, the advice goes -- never be weak, vague or old-hat. Vengeance/Hell/Lawless Valley permutations have had their day. Come See Me Hang is an arresting title for a western and

one which evidently appeals to BHW author Paul Wheelahan. In 1975,

he used it when penning a Cleveland paperback under the pen-name Brett

McKinley. The book told the story of young attorney Shell Tregarno,

who received via telegraph the brief, callous "come see me hang" message

from his n'er-do-well father, and a little later learned it was too late,

because pa had been lynched by a mob. In July, the title will be appearing

again, on a BHW under Paul's Chad Hammer byline. The new story features

as a central character a gunfighter called Ryan Bodie -- a name with

which Paul's readers will also be familiar, since he has previously used

it as a BHW pen-name. The blurb says, "Bodie would survive. He always did.

He was that kind of man." Well, he surely has survived, albeit in a changed

rôle!

|

First time around.

First time around.

|

New gateway.

New gateway.

|

Black Horse Westerns continue to enhance their presence on the Net. The

previous edition of this quarterly online magazine attracted more visitors

in two months than any previous edition in a full three. And on April 20,

publishers Robert Hale launched a much improved company website.

The bright new pages at www.halebooks.com offer secure, online

shopping facilities and competitive prices. BHWs are well represented,

with cover images and details for more than 200 titles, shrugging off the

"poor cousin" status afforded them in the print catalogues of bygone times.

Specialist site designers Ehaus say, "We believe that a publisher's website

should be more than a pale imitation of its print catalogue. It should serve

as the definitive source of authoritative and enhanced information on the

company's products."

|

|

|

Greg Mitchell puts us on target

A PRIMER IN REALISTIC BALLISTICS

"See how you like this you sheep-herding sonsofbitches."

He fired both barrels [of a sawn-off shotgun] into the approaching

riders. Eighteen large slugs tore into horses or men. Corbett's horse reared

straight over backwards. Tom Casey dropped his rifle as he was hit in the

right upper arm. Grazed by a slug, Mike Casey's horse started to buck and

collided with that of Perez. Suddenly all was confusion with plunging horses

and startled riders milling about.

Had Norris waited until his targets were closer, the shots would have

been more devastating but round balls fired from smooth bores lost power

rapidly after thirty yards and wounded rather than killed.

Warbonnet

Creek

Greg Mitchell

THE average nineteenth-century westerner was not a quick-draw artist.

He wouldn't compromise safety in carrying his gun by using a specially

made, loose holster likely to lose the gun while mounting or dismounting

from a horse or struggling with big calves at branding time.

Myth and reality exist side by side in many a western, in print or on

screen. But the tied-down holsters worn by fictional heroes and villains

were unknown until the US Army started tying down their automatic pistols

long after the Wild West was gone.

The working cowboy wore his gun fairly high on his hip where it would

not get in his way when riding or working on foot. The holsters were deep,

and in some cases tight-fitting, and the loop over the hammer spur that

crept into 1950s television westerns was not necessary.

The many photos of lawmen and cowhands taken in frontier times never show

a tied-down holster or a hammer thong.

The Texas Rangers, favoured by western pulp magazine writers and

readers of later times, had more than their share of gunfights. My own next

BHW, Red Rock Crossing, will tell of two Texas Rangers held

up by a flood. They have with them a prisoner -- a man fleeing a range war

and a sinister hired killer called Missouri Sam. And an important twist

in the story involves a gun.

For now, what I can reveal is that Texas Rangers didn't rely on quick

draws. They had a practice of always drawing their weapons before going

into dangerous situations. Survival was not a sporting event. Speedy draws

were no good without accuracy. In many documented gunfights, the first

shots were hasty and usually missed.

Intentionally shooting guns out of opponents' hands was virtually

impossible because shooter and target were both moving and there was no

time to aim, let alone calculate the correct amount of muzzle elevation

for the range. A revolver sighted to hit the point of aim at 50 yards would

place its bullets a little higher inside that range. It would make little

difference on a man-sized target but something as small as a man's hand

or a gun would most likely be missed. In life-and-death situations men usually

shot for the largest part of their adversary. A wound that slowed or disabled

an opponent was better than a clean miss because fancy shooting went wrong.

Revolvers are not easy to shoot because of the short sight radius and

the tendency to pull the weapon sideways if the trigger is not squeezed carefully.

Under favourable conditions, a trained revolver shot with a good weapon

can hit a man at 50 yards but the average shooter in a gunfight is more

likely to miss. Firing from horseback it would be good shooting to hit a

man anywhere at 10 yards' range.

A man holding back the trigger and fanning the hammer of a gun would

not be able to shoot accurately past a couple of yards. Nor can a man fire

two guns simultaneously and hit two different targets.

Revolver shots do not disembowel people or blow heads off. The study

of ballistics was only in its infancy in the nineteenth century and many

revolver bullets actually were under-powered.

The derringer, the pocket-sized gun featured by so many western writers

was a very poor weapon. The famous Remington over-and-under derringer fired

the .41 rimfire cartridge. Across a card table it was capable of killing,

but the cartridge was very low-powered and had been known to bounce off

trees at 15 yards. Most small revolvers and derringers were made of inferior

metal for lightness and their cartridges were low-powered to avoid blowing

up the guns. Because of the small grips and inadequate sights, derringers

were not accurate except at very close range.

Some writers like to introduce exotic weapons into their stories, but

ammunition for some of these would not be readily available on the frontier.

The Colt .45 and the Winchester repeating rifle were very popular, reliable

weapons so authors do not lack originality by using them in their stories

as long as they are used within the right time frames -- from 1866 with

the first model Winchester and from 1873 with the Colt .45.

The Wild West era was virtually over before high-powered rifles

became available to civilians. A high-power cartridge was one that travelled

at 2,000 feet per second or faster. The powerful rifles of the black-powder

era pushed their heavy bullets along somewhere between 1,400 and 1,600

feet per second and used much heavier bullets. They could throw bullets

up to a mile but because of their high trajectories accurate shooting was

only possible when the range was correctly calculated and the sights set accordingly.

Rifle shots at people more than 300 yards away were very difficult

with the Winchester repeaters and other carbines that were so popular

in the Old West. At that range the front sight almost completely covers

a man. A good shot using a rifle he knows, can still hit him, but cannot

guarantee where the bullet will strike. Different shooters hold their rifles

differently and not all are sighted exactly the same. A good shot using

a strange weapon could still miss. Telescopic sights were available as were

long-range target sights but these were not carried by the usual westerner.

They saw some use though among buffalo shooters and other professional hunters.

The killing range of a shotgun using shot cartridges is normally about

40 yards. If the weapon is sawn off, the lethal range would be about 30

yards as the shot is less concentrated. Heavy shot, like buckshot had a greater

killing power than light bird shot. But because the pellets are round and

not spinning like rifle bullets, all lose their velocity very quickly.

The main killing area of a shotgun is about a 30 inch area where most of

the shot is concentrated. A blast from a shotgun in not going to mow down

three or four men at 40 yards although it might seriously damage two.

Close-range shotgun blasts do not cut people in halves but they can

inflict terrible wounds. Shot spreads roughly 1 inch per yard that it travels.

The greater the distance, the less concentrated is the impact of the shot.

Heavy buckshot balls were around .30 calibre and at close range hit with

a lot of power, so sometimes one pellet in the right place could be fatal.

The advantage of a shotgun was that the spread of the shot gave the

shooter a good chance of hitting his target even if most of the load missed.

A shotgun is not likely to be destructive over a wide area because by the

time it has spread widely, the pellets are losing their power. But at 30

yards it will cover an area that could be three feet wide and still deliver

killing velocities.

The western writer who finds a hazy knowledge of firearms daunting cannot

take easy refuge in other weapons.

Knives were used occasionally in the Old West, especially in the days

of slow-loading percussion firearms, but it is doubtful that too many people

were seriously hurt by thrown knives. A knife, thrown over any distance,

turns end over end and unless the distance between target and thrower

is carefully measured, there are long odds against it hitting point first.

Even if it does, the knifepoint is likely to be deflected by clothing or

even ribs. A thrown knife point should strike vertically in relation to

the ground and is unlikely to penetrate a person's rib cage.

The Indians were aware of this and fitted the heads on their war arrows

horizontally to the ground so that they slipped between ribs. An arrow would

have more power than a thrown knife. A fatal wound from a thrown knife could

happen but the chances of the victim being killed by lightning would be considerably

higher!

Westerners were familiar with all kinds of whips, from light riding

whips up to heavy bull whips, and would know that whips were very poor

weapons. With a conventional whip the real damage is inflicted by the soft

cracker on the end that moves at supersonic speed if the whip is used correctly,

but even that is unlikely to do serious damage. Whips cannot be used indoors,

nor can they be brought into action quickly. A whip with a plaited thong

more than seven feet long is slow and awkward to use. The length of a whip

has little effect on its impact but whips do not break bones or kill people.

Given the time and space to use it, a real expert with a whip might do some

very minor damage . . . but a man with a whip who goes against someone with

a gun is confusing his ambitions with his capability.

-- Paddy Gallagher, aka Greg Mitchell, whose next BHW,

out in July, is Red Rock Crossing.

|

Derringer

Derringer

|

|

Steps to put writers on the right trail

LET'S DO THE TWIST!

Candice Proctor is not a western writer. Her sister is! But

of more immediate importance is that she has an excellent blog, csharris.blogspot.com,

where she comments from time to time on aspects of fiction of interest to

writers and readers in all genres. Past entries have covered plotting, characterization

and writing a synopsis. Candice describes herself as a former university

professor with an incurable case of wanderlust, who writes historical mysteries

under the name C.S. Harris and thrillers as one half of Steven

Graham. She has also written historical romances.

Here is a short sample of her writing about writing that could be followed

to put extra zing into most anybody's next BHW. . . .

I’VE been giving some thought lately to twists. You know, those places

in a book or movie where the story takes off in a (hopefully) unanticipated

direction, where the reader/audience says, “Wow! I didn’t see that coming.”

It seems to me that twists ought to be quantifiable. I guess it’s the academic

in me, always analysing and trying to compartmentalize things. But what is

a twist, at its most basic, except a bit of information the protagonist (and

reader) has that turns out to be wrong? Some of the most common twists are:

-

Someone the protagonist thinks is a friend turns out to be an enemy.

- Someone the protagonist thinks is an enemy turns out to be a friend.

- Someone we think is dead turns out to be alive.

- Someone we think is alive turns out really to be dead.

- Something believed lost is not really lost.

- A character’s supposed motive is seen to be impossible.

- A character has a motive that was never suspected. (This doesn’t apply

only to mysteries; think of romantic comedies where the hero woos a woman

on a bet.)

- A family relationship turns out to be different from what was believed

(an “aunt” turns out to be a mother, a child discovers he’s adopted, etc).

-

A character we think is a man turns out to be a woman, and vice versa.

I’m sure there are many, many more variations on the theme. So how about

it? What can you add to the list?

|

|

|

|

|

|

NEW

BLACK HORSE

WESTERN NOVELS

(Published by Robert Hale Ltd, London)

978

| Incident at Coyote Wells

|

Logan Winters

|

0 7090 8285 9

|

Tombstone Lullaby

|

Walt Masterson

|

0

7090 8253 8

|

Carson’s Revenge

|

Jim Wilson

|

0

7090 8353 5

|

Savage Rides West

|

Sydney J. Bounds |

0

7090 8347 4

|

The Gold Mine at Pueblo Pequeno

|

Will Keen

|

0

7090 8359 7

|

Shootout at Big King

|

Lee Lejeune

|

0

7090 8366 5

|

The Iron Roads

|

Caleb Rand

|

0

7090 8360 3

|

Too Fast to Die

|

Dempsey Clay

|

0

7090 8374 0

|

Catfoot

|

J. William Allen

|

0

7090 8375 7

|

Vengeance Unbound

|

Henry Christopher

|

0

7090 8376 4

|

Come See Me Hang

|

Chad Hammer

|

0

7090 8265 1

|

Stampede at Rattlesnake Pass

|

Clay More |

0

7090 8383 2 |

Bluegrass Bounty

|

Jack Reason

|

0

7090 8384 9

|

Christmas at Horseshoe Bend

|

J. D. Kincaid |

0

7090 8381 8

|

Rolling Thunder

|

Owen G. Irons

|

0

7090 8382 5

|

Bitter Blood

|

Clint Ryker

|

0

7090 8387 0

|

Morgan's War

|

Henry Remington

|

0

7090 8391 7

|

Trouble at Brodie Creek

|

Ben Coady

|

0

7090 8399 3

|

Mayhem in Hoosegow

|

M. Duggan |

0

7090 8401 3

|

Massacre at Empire Fastness

|

P. McCormac

|

0

7090 8400 6

|

Misfit Lil Fights Back

|

Chap O'Keefe

|

0 7090 8176 0

|

Shootout at Owl Creek

|

Corba Sunman

|

0 7090 8341 2

|

| Brannigan

|

Bill Williams

|

0 7090 8378 8

|

Red Rock Crossing

|

Greg Mitchell

|

0 7090 8419 8

|

Knife Edge

|

Tyler Hatch

|

0 7090 8416 7

|

Winter Kill

|

Frank Roderus

|

0 7090 8430 3

|

Massacre at Bluff Point

|

I. J. Parnham

|

0 7090 8424 2

|

Warwick's Battle

|

Terrell L. Bowers

|

0 7090 8423 5

|

Man on the Border

|

Dave Austin

|

0 7090 8435 8

|

Death at Bethesda Falls

|

Ross Morton

|

0 7090 8432 7

|

|

|

|

Ten new titles are

issued every month as BHWs -- tough, traditional or,

sometimes, off-trail. The brand caters for all tastes.

Black

Horse Westerns can be requested at public libraries, ordered at bookstores,

and bought online through the publisher's website, www.halebooks.com, or retailers including Blackwells, Amazon UK, WH Smith and VinersUK Books.

Trade inquiries

to: Combined Book Services,

Units I/K, Paddock Wood Distribution

Centre,

Paddock Wood, Tonbridge, Kent TN12 6UU.

Tel: (+44) 01892 837 171 Fax: (+44)

01892 837 272

Email: orders@combook.co.uk

|

|

|

|

|

|