|

March-May 2007

|

BLACK

HORSE EXTRA

Detectives in Cowboy Boots

Hoofprints Ending with a Bang

Farewell to a Small Giant

New Black

Horse Westerns

One year when sales of western novels hit a worrying low, a publisher

advised a contributor, "If an author has confidence in his writing ability

he should tackle something more demanding than the short western, and certainly

from Elmore Leonard onwards there are writers who have made a successful

transition."

He was partly wrong and partly right. Done properly -- with attention

to the standards of plotting, characterization, background research and

narrative skill that should apply to all genres -- the western is as "demanding"

as any other fiction, maybe more so when it comes to achieving the delicate

balance between historical reality and myth. He was right with his mention

of Elmore Leonard. He might also have named Erle Stanley Gardner, John D.

MacDonald, John Jakes and Loren D. Estleman among others, though the crossovers

have not always been in one direction.

Traditionally, advances on westerns have averaged less than novels in other

categories. Reports today are that a publisher will pay four times what he

pays for a western for a historical romance. Granted the latter, with similar

research demands and similar calls for set-piece scenes, will run to more

pages, though not four times as many, and will carry a higher cover price,

though not four times higher.

Just as galling is the notion buyers of hardcover and trade-paperback westerns,

usually public libraries, don't give a hoot for the credentials of individual

writers; that they buy by publisher's imprint and price. The readers of

westerns, it's alleged, are too shy to communicate preferences, or don't

have them.

In this issue, we can read Chap O'Keefe's memories of authors who moved

competently between thriller and western fiction and whose books were widely

enjoyed. A second feature provides useful research information on a firearm

popular with western writers -- the Walker Colt. Sift through the legends

and the facts with Greg Mitchell.

Enjoy, too, the Hoofprints section, and

feel free to leave your own impressions at feedback@blackhorsewesterns.com.

Lastly, sadly, we must mark the passing of writer Sydney J. Bounds -- a grand

old man of genre fiction (and Black Horse Westerns) who died in late

November.

|

|

|

Chap

O'Keefe on writers who ride for two brands

DETECTIVES IN COWBOY BOOTS

Where was Emily Greatheart? The pretty young lady from Denver had gone to Arizona to meet her dead fiancé's mother

and vanished. Only a bloodstained jacket was found in an abandoned spring buggy hired from the Pike's Crossing livery stable.

Emily was the daughter

of Big Jack Greatheart, ex-marshal and one-time tamer of brawling boom-towns.

But Big Jack lay in his bed in Colorado, frustratingly crippled by arthritis

and a skeleton of his former self. So he called on unconventional detective

Joshua Dillard.

Joshua followed a cold trail

and hot impulses into battle against ambitious cattleman Bart Waller and

his gun-handy, womanizing son, Vincent. No wonder he was soon up to his reckless

neck in two-fisted, lead-slinging trouble!

STRIP out the western trimmings from what is the

back-cover blurb for Sons and Gunslicks, a new Black Horse Western out in March, and you could well have the bones for

a typical private-eye story with its origins in pulp fiction.

This would be far from the first time links have

been pointed out between crime stories and westerns. Just as significantly,

a complete run-down on the authors who have written both would .

. . well, fill a book of the bibliographical kind. But we can run some

words and pictures designed to encourage a look with a fresh eye

at BHWs and the tradition they represent.

|

|

|

A lately neglected author who comes to mind is

Frank Gruber (1904-1969). He wrote in quantity for both the western

and detective titles during the golden years of the pulps. He also scripted

at least a couple of Universal's revered Sherlock Holmes movies

starring Basil Rathbone as the great detective and Nigel Bruce as

his Watson. Made on low budgets in Hollywood during World War II,

Terror By Night and Dressed to Kill (aka

Prelude to Murder) are now in the public domain and have

been reissued several times on DVD packs of varying quality. They are

fun nostalgia, often at a modest price. (But a conductor on a

London-Edinburgh express. . .?)

If only a western movie will do, why not hunt out 1955's Rage

at Dawn, another classic widely available on DVD? It's based

on Frank Gruber's fictionalization of the story of the Reno Brothers gang

and stars Randolph Scott, Forrest Tucker and J. Carrol Naish. Scott plays

James Barlow, a detective agency operative sent from Chicago to infiltrate

the gang.

|

|

|

Gruber's twentieth century detective creations, featured in crime

novels worth tracking down, were Simon Lash and Eddie Slocum, Johnny

Fletcher and Sam Cragg, and Oliver Quade.

For the large and small screens, Gruber reputedly wrote more than 200 scripts or scenarios, mainly

westerns. He created several television series, notably Tales

of Wells Fargo, The Texan, and Shotgun Slade (1959-61). The last combined his favourite genres: Slade

was a private eye in the Old West.

Another prolific crime and western writer of the same period was William

Ard. He was mentioned not long ago by James Reasoner at his absorbing

blog, Rough Edges. James is a writer with a sure foot in both camps today;

Ard was the private-eye tale-teller with the Timothy Dane and Lou Largo

series who, under the name Jonas Ward, created the long-running Buchanan

westerns.

Ard wrote the first five books featuring Tom Buchanan, one of which was made into a movie in 1958, again

starring Randolph Scott. Buchanan Rides Alone

was filmed tongue-in-cheek by famed western director Budd Boetticher,

based on the novel The Name Is Buchanan.

|

|

|

Ard died during the writing of the sixth Buchanan book,

and it was completed by science-fictioneer Robert Silverberg.

The series was continued by Brian Garfield, another writer now

also renowned for crime fiction, who contributed Buchanan's

Range War before William R. Cox took over with titles including

Buchanan's Stage Line.

Buchanan had a memorable pard in Coco Bean, a prizefighter,

holding the title Black Champion of the World.

|

|

John Hunter

John Hunter

|

In Britain, writers of light fiction made similar crime/western crossovers through the years.

Veteran John Hunter (1891-1961) was a key contributor to the

Amalgamated Press's Sexton Blake Library detective series well into

the 1950s.

As a boy, I developed a taste for Hunter's tightly written, exciting stories which tempted me to sample his

Lannagan novels for the same publishing company's Western Library.

They appeared in identical, inexpensive format -- two slim paperbacks

a month with digest-sized, newsprint pages. The westerns had vigorous

covers by James E. McConnell or Derek C. Eyles.

|

|

Rex Hardinge

Rex Hardinge

|

The Lannagan novels were accompanied by Western Library's reprints of the likes of Ernest Haycox, Max

Brand and William Macleod Raine. Among other British crime writers

contributing were Rex Hardinge, T.C.H. Jacobs and Sydney J. Bounds.

Rex Hardinge, like Hunter, was a Sexton Blake

author. He was renowned for his stories set in India and Africa which

he knew from first-hand experience. During World War II, Hardinge

served as an officer in Military Intelligence. He was parachuted

into China in 1942, remaining there until 1946 with "a cloak and

dagger outfit".

He wrote his westerns as Rex Quintin and Charles Wrexe. More can

be read about him at www.sextonblake.co.uk, the absorbing site put together by Mark Hodder.

|

|

T. C. H. Jacobs

T. C. H. Jacobs

|

Crime writer T. C. H. Jacobs (1899-1976), aka Jacques Pendower, Penn Dower

and Tom Curtis, wrote original Western Library novels about a Texas marshal

called Whip McCord, starting with Texas Stranger. I believe several were later reissued in hardcover versions by John Long Ltd.

From 1960, Jacobs's publisher for crime novels was Robert

Hale Ltd. The Perfect Wife, published by Hale in 1962

under the Pendower name, features Slade McGinty, a private eye with an

office-cum-flat in Brewer Street, Soho. McGinty is commissioned to seek

information about the young, popular and charming Lady Sandra Bondell,

who "sounded more like a saint than a modern young woman. Too damned good

to be true."

|

|

|

Vintage detective novels by Jacobs published in the 1930s (US, Macaulay;

UK, Stanley Paul) are listed by Allen J. Hubin as genre classics.

Jacobs had a keen interest in medical jurisprudence, also writing

true-crime articles and books. And interest in criminal psychology could

be put to use in a western, too, adding depth to plot and characterization:

"Slim, he thought, was not to be trusted with any lethal weapons.

Such concentrated hatred in one so young fascinated Whip. He wondered

if there was anything in heredity. Lefty Masters had been a killer. So,

it seemed, was his son. Or was it merely environment? Slim would have

been reared in the company of outlaws. He must inevitably have absorbed

their anti-social thought and actions."

|

|

|

In the 1960s, when I was an editor for Micron Publications

and Odhams Books, I asked Jacobs to contribute material and came to

know him through letters and phone calls. Eventually, Jacobs invited

me to lunch at the Wig and Pen Club in Fleet Street. Despite big differences

in age and background, it consolidated a rapport. Born in Devon and

living in Kent, Jacobs was a soldierly, no-nonsense gentleman who called

a spade a spade in a voice that was gentle and gruff at the same time.

Sadly, commercial fiction today supports very few craftsmen of his kind.

His experience was wide and long -- the army,

the civil service, radio, film, Rotary, the Crime Writers' Association.

. . . Jacobs's novel Traitor Spy was filmed in 1939-40,

starring Bruce Cabot and released in the US as The Torso

Murder Mystery. For D.C. Thomson, the periodical publishers

based in Dundee, Jacobs was the author who wrote possibly the largest

number of detective stories featuring Dixon Hawke, the company's

rival to Sexton Blake. Jacobs produced most of the Hawke serials that

appeared in the weekly Adventure in the 1930s as well

as stories for the annual Dixon Hawke Casebook.

In 1949, for the Amalgamated Press, Jacobs wrote a western text series for Knockout paper, Buffalo

Bill -- Frontiersman. In December a year later, it was

back to detectives for the same firm's Sun, with a

series about Tough Tempest -- Crime Buster -- launched

in that publication in the same issue as Barry (Joan Whitford) Ford's

Law of Wild Bill Hickok series.

I suspect Jacobs's work may not be valued completely in his

home country. Today, perhaps the finest store of his literary papers

and manuscripts is kept in the Special Collections Library of Pennsylvania

State University.

|

|

Sydney J. Bounds

Sydney J. Bounds

John Creasey

John Creasey

|

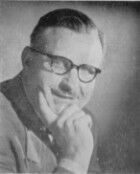

Another prolific "old hand" I worked with,

Syd Bounds, wrote for Western Library as James Marshal, and while

his speciality was science fiction, he could turn his hand

to just about anything, including crime stories. In recent years,

Syd wrote the Savage series of BHWs. A Man Called Savage

is to be reissued by Ulverscroft in large-print this summer, joining

Savage's Feud and making at least a couple of his westerns

more readily available to US readers.

Also writing both crime and western fiction

in the '50s was Vic J. Hanson. His crime yarns were gangster fiction

of the Hank Janson kind, but he later turned to Sexton Blake detective

stories. And then came many, many Hale westerns under

his own name and Jay Hill Potter.

Hanson, Bounds, Jacobs and Hardinge all accepted

invitations to write for me in the '60s when I was editing

Western Adventure Library, Cowboy Adventure Library and

-- in the crime line -- Edgar Wallace Mystery Magazine.

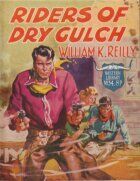

John Creasey (1908-1973) --

of Toff and Gideon fame, prolific author of hundreds of crime

novels -- wrote about 30 westerns in the 1930s and '40s as

William K. Reilly, Tex Riley and Ken Ranger. Once, he made the mistake

of mixing up coyotes with buzzards or vultures. Because he was British,

he was never forgiven for the "flying coyotes". Some US editors

and literary agents didn't just laugh. They used the famous gaffe for

years as grounds to reject automatically all westerns written by Britons

-- notwithstanding Creasey wrote his, for him, small bunch in probable

haste and difficult circumstances without the benefit of the research

and reference books available today, let alone the Internet.

|

|

|

Meanwhile, "indigenous" writers --

an agent's adjective, not mine -- were allowed to survive unscathed

sins of poor research similar to Creasey's. For example, as late

as 1990, a respected western/crime writer could set his novel in

1901, write of a character anachronistically "zipping up his pants",

yet continue to receive the critics' adoration in august trade journals

such as Publishers Weekly and Booklist,

and later have the work in question anthologized as one of the great

stories of the American West. (Which it is, by the way.)

I hold no brief for John Creasey, beyond

objection to the mean-spirited exclusion of anyone, but I did have

a strong appreciation of his crime novels, which gave me countless

hours of enjoyment in teen years and earlier. Copies of his westerns,

as will be seen, I didn't come across in my youth. It was only late last

year that I had the lucky chance to buy one. They are in the rare books

category. Thus they change hands at prices way beyond the means of those

who primarily read westerns rather than invest in them as collectibles

or trophies from eBay hunts.

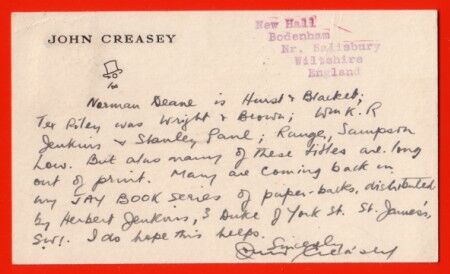

The Creasey western I read recently was a

Western Library reprint of Riders of Dry Gulch,

which avid Creasey bibliographer Richard Robinson records was

originally published by Herbert Jenkins Ltd in 1943. Confirming this,

I have in my files the handwritten note below which Mr Creasey

sent me in 1958. The author lists the publishers for one of his

mystery personas and his three western identities . . . and regrets

that the westerns are, even then, out of print. None of them ever did

reappear in the Jay Books paperbacks he mentions.

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Dry Gulch novel's main drawback

is adherence to a common practice of its age -- trying to convey

supposedly western dialect through bizarre spelling. Clarity is

sacrificed on occasion to no good purpose in the "jumpin' jack-rabbits"

dialogue. Some might also find a lack of authenticity in the Texas setting.

Particularly, the chapters set in El Paso would require, for today's

knowledgeable reader, greater research attention. But bursts of action

are frequent and, despite a little meandering in the storyline along

the way, a villain is unmasked in the last chapter. Mystery elements

feature as prominently as in the Creasey crime novels of the period

-- the Peter Mantons, Norman Deanes, Anthony Mortons, Gordon Ashes

and so on.

A good man is framed and persecuted; an eccentric

runs loose. You are left in no doubt about what kind of story

you are reading when lawyer Petrie tells cowboy hero Boyd Warren

in an early chapter, "I'm a long way happy 'bout Long Paul. Is he more

than he pretends? Is his queerness acted? Answer that, and maybe yuh'll

answer a lot more. Ther's plenty that want answerin' in Dry Gulch.

If Olsen was wrongly convicted, as I think, ther's a man at large,

more than one man, I know, but one who organised these killings and

lootings. Since Olsen left, there has been none of them, but I live in

constant dread that they will break out again."

Maybe for the people who read and wrote in

wartime Britain, a mystery novel set in a faraway Old West

provided a more complete escape than a novel placed in a society

and against a background where familiar detail couldn't help but

remind them, along with the nightly air raids, that the way of life

they cherished was under appalling threat. Quaint (wistful?) mention

is made in Riders of Dry Gulch of steak "juicy-looking,

sizzling in the heat", bacon and eggs, chickens on spits and a smell

of frying steak.

Before World War II, in 1938, Creasey had

dedicated the novel Introducing the Toff, published

in hardcover by John Long Ltd, to the Amalgamated Press man who

later edited both the Sexton Blake and Western Libraries. The dedication ran,

"To L. E. Pratt, who first put the Toff into print."

|

|

|

Richard Robinson told me a few years ago, "John's westerns

are like the Holy Grail -- and some of the harder books to find. At a recent

get-together [of a group of Creasey enthusiasts] we had just over a half

of them in various editions. Several were published in magazine form in the

US and are more common."

Though Creasey's reputation rests on his hundreds

of crime novels, I think he maintained a pride in his western

writing after it became unobtainable. He was an assiduous publicist

and in the late '50s issued a greetings-style card to his reader

correspondents with the title "Creasey books are on top of the world

. . . and here are some of the reasons why". In it is the sentence:

"He is the only English member of Western Writers of America." Which

should have been qualification enough to clip the wings of any patriotic,

wild-west high-flyer objecting to sharing his air space with coyotes!

|

|

Jack Trevor Story

Jack Trevor Story

|

Among the later Sexton Blake writers who

also wrote, or had previously written, westerns was the much

under-rated Jack Trevor Story, author of The Trouble With

Harry, filmed by Alfred Hitchcock, and Live Now,

Pay Later. Story's "rather good westerns", as he described

them, were mostly about a character called Pinetop Jones and were

published in the '50s, usually in hardcover for the lending library

trade, by Hamilton (Stafford), originators of the Panther Books

paperbacks. When I was in London copy-editing Sexton Blake novels

for the Amalgamated Press in the early '60s, I was completely unaware

that Story had also been western authors Bret Harding and Alex Atwell.

On the back cover of a Panther Books hardcover,

Harding's author bio says, "He has always been interested in

the genesis of the western novel, especially those in which character,

humour and genuine suspense take precedence over the stereotyped

horse opera plot." Mystery, romance and intellectual eccentricity

are also mentioned. Anyone who met Story, or has read his work or

about him, knows something of the last! To sample an opening chapter

from a quirky Jack Trevor Story western go to http://www.jacktrevorstory.com/pinetop_jones.htm

. The entire website is an excellent tribute.

|

|

Terry Harknett

Terry Harknett

|

By the end of the Swinging Sixties,

few British crime writers were left dabbling in westerns, or

admitting they once had. Then came the '70s and the influence of the

Italian movie makers with their violently dramatic, spaghetti westerns.

A younger generation of British writers took on board the lessons. Terry

Harknett, a self-confessed "frustrated mystery writer" with "no particular

penchant" for westerns, slipped into the scene almost by accident.

"For fifteen long years I wrote mystery novels

[for Robert Hale Ltd] that were published twice yearly -- and

sank without trace at the same rate," he told the US magazine The

Writer.

Luck took a hand, he said, when he was hired to write a "book of the

movie" and it happened to be a western. "I had not seen it and I had

never read a western novel."

But the rest is history. He did a few more; it

was realized nobody was writing books like the tough spaghetti

movies; he assumed the pen-name George G. Gilman, and the famous

Edge paperbacks came into being.

Soon, every paperback publisher in London had

an Edge-series clone. The stories were written almost exclusively

by a coterie of writers who followed, perhaps unknowingly, in

the tracks of an existing tradition of writers "who hadn't been

further west than Paddington Station". They won themselves a higher

profile than the forgotten British western writers of earlier decades

and became known as the Piccadilly Cowboys. Among them were John

B. Harvey and Mike Linaker.

John Harvey's books had the trademark of the

PCs which was gritty realism, the more sordid it could be made the better:

"Wes Hart woke sticky with sweat that lay on his body like cloying vomit,

turning cold." Harvey did the opposite to Terry Harknett -- he later

headed completely away from his fascinatingly ugly westerns, about

Hart the Regulator, to write bestselling crime novels about Detective

Inspector Charlie Resnick.

Mike, as Neil Hunter, Richard Wyler and John C. Danner, still rides

the range for Black Horse Westerns and the large-print Linford Western

Library, while his bill-paying work is blockbuster adventure thrillers

for Gold Eagle's series based on Mack Bolan lore.

|

|

Mike Stotter

Mike Stotter

|

Associated at an early stage with producing a

fanzine for Harknett's GGG fans, another Mike -- Mike Stotter

-- graduated to writing westerns of his own. In 1997, Ed Gorman

and Martin H. Greenberg chose an extract from Mike's first BHW,

McKinney's Revenge, for inclusion in The

Fatal Frontier. This was a 420-page anthology in which

Gorman and Greenberg demonstrated the direct links between crime

fiction and western fiction, proving the contention with a fine collection

of stories from Elmore Leonard, John Jakes, Brian Garfield, Marcia

Muller, James Reasoner and other top-selling crime and mystery

authors. Today, Mike continues with occasional western projects,

but he is also highly respected as the editor of the crime fiction website

Shots ( www.shotsmag.co.uk).

|

|

|

To compile a complete history of the parallels

between hardboiled detective stories and westerns would be

beyond my capabilities and take space unavailable here. But I will

add that a lifetime's enjoyment of tightly plotted crime thrillers ensures

I'd be less than satisfied with writing a Chap O'Keefe western which

didn't contain mystery and suspense. For stories about the series character

Joshua Dillard, an ex-Pinkerton detective, the elements are routinely

accommodated. The Gunman and the Actress and The

Lawman and the Songbird attempt a pattern set by genre classics.

So, too, do Shootout at Hellyer's Creek, The Sandhills

Shootings, Ride the Wild Country and this month's

Sons and Gunslicks. Every time, the intention has been to spring

plot surprises and solve puzzles in the closing pages of action-packed

yarns.

My other series character, Misfit Lil, similarly

encounters situations more common to crime stories. In one forthcoming

title, Misfit Lil Hides Out, she is framed for murder.

As always, resourceful Lil makes some ingenious plays and produces

the necessary answers to a mystery with a flourish at the end.

|

|

|

To wrap up, let's return to Frank Gruber

with whom we started. The aim here -- in case detractors are itching

to level the charge -- has not been to paint a picture of a cosy club of forgotten

old fogies. Way back in January 1941, Gruber made the following

comments, in which you could substitute "western" for "mystery" all

the way through:

"The manager of a large book store gave me

an advance copy of a mystery novel by a new author and asked

me for my honest opinion of the story.

"It started off swell. The detective

was a colourful character. The writing had a vitality you

seldom find, the dialogue was crisp and the story moved.

It lacked only two things, but those two things meant all the

difference between an outstanding mystery and 'just another mystery

novel.'

"The story lacked a theme and it lacked invention. All right, nine

out of ten mystery novels lack those two very same things. That’s

why they sell their 2000 to 3000 copies and are forgotten. A dozen

or so mysteries stand out every year from five hundred that are

published. In practically every case these outstanding mysteries

have both theme and invention.

"In a previous article in the Writer’s Digest I stated my

opinion that a colourful theme was vital in a bestselling mystery

novel. I still hold that to be true, but now I add that without

invention the theme falls flat. . . .

"All detective stories have the same basic

plot. A murder is committed, perhaps two or three; questions

are asked and answered and your detective makes certain deductions

and eventually pins the guilt upon the culprit.

"Every detective story writer has to work

from his skeleton plot. The dressing he gives it is what makes

his story different from other detective stories. But too often

this dressing is commonplace. The jaded detective story reader

has read essentially the same thing a hundred times. Murder

in itself is no longer startling or unusual.

"That is why the smart detective story

writer gives his story invention.

"In my own case, I try to have a minimum

of six or seven inventions in a novel and I try to space them

out so there’ll be one every two or three chapters. . . .

That is exactly why this story falls flat on its appendix. It has

nothing different in it, nothing unusual. It lacks both theme and

invention."

Some advice is timeless. I hope, as either readers or writers, we can count on theme

and invention being among the ingredients in many of today's Black Horse

Westerns.

-- Keith Chapman, aka Chap O'Keefe, whose

latest BHW is

Sons and Gunslicks.

|

|

Big fan of westerns. Big fan of westerns.

|

An

assortment of the

right tracks

HOOFPRINTS

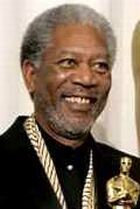

Morgan Freeman co-starred with Clint Eastwood in the

actor-director's acclaimed western Unforgiven, but he's determined

at age 69 not to retire until he has done another. He told Big Picture News

Inc, "I haven't even scratched the surface. There is great stuff that hasn't

been touched by me ... I'm a big fan of westerns, and I haven't

done my ultimate one. There are many stories to tell." Freeman, an Oscar

winner, has played widely diverse roles, including several

detectives, a convict and a poor black chauffeur, but he has expressed

in the past an eagerness to complete the list by playing a deputy marshal

from the 1870s. "No one knows about the law officers who populated the

West -- the deputy sheriffs, deputy marshals and people of that ilk who

were in Texas, Oklahoma and Arkansas. This guy's name was Bass Reeves

and he was a true character. It has been in the pipeline for years and

it's something I really want to do, but we have a problem getting the

script together. That's the hardest part of any movie." Come in, Adam

Wright. . . ? In 2001, Adam fictionalized Reeves's story for a BHW

novel.

|

|

|

Thought mixing horror with westerns was a new development?

Think again! Los Angeles Times "resident expert" Kenneth Turan

listed among "notable DVD offerings in film" Creepy Cowboys:

Four Weird Westerns. He said The Rawhide Terror,

Tombstone Canyon, Wild Horse Phantom and Vanishing

Riders were examples from the 1930s and '40s of westerns with

pronounced horror/mystery elements. Stars included Tom Mix,

Ken Maynard, Buster Crabbe and Bill Cody. Another

reviewer said. "So old they creak, but man oh man, are they fun." Not

bizarre enough? Turan also recommended Westerns With a

Twist, a trio of full-colour westerns -- Apaches,

Chingachgook — The Great Snake and The Sons of

the Great Bear. These movies were made in East Germany during

the Cold War years -- "Red Westerns" -- and star a Serbian actor, Gojko

Mitic, as a heroic Native American battling perfidious white settlers.

|

Screams of laughter.

Screams of laughter.

|

Roped in.

Roped in.

|

Avalon Books

is a US publisher of wholesome adult fiction. "Substitute euphemisms in

all instances where profanity, including 'damn' and 'hell', might be used,"

its rules for writers say. On the back of a title issued in the mid 1980s, the firm listed 38 of

its westerns. They included no less

than 15 by Terrell L. Bowers. Today the veteran author is a valued

contributor to the BHW series who made his first entries in the line's debut

year, 1986. He told Avalon he sometimes thought he was born with boots

and spurs. His father was his inspiration. He provided Terrell with his

own horse and cows to ride and rope. On small acre lots or fair-sized farms,

he always had the fixings for cowboying on hand. Terrell also shared his

father's taste for movies starring Bob Steele, Johnny Mack Brown, Roy

Rogers and John Wayne. Western blood was in his veins, and he

loved to create a new story, new characters -- then let his imagination

run wild. "Fortunately," he once wrote, "I have a beautiful, loving wife

and two angelic girls, who understand and accept my endless hours at a typewriter.

My principal desire is that somewhere there are western lovers who find

my stories entertaining." His latest BHW is The Trail to Yuma.

|

|

|

Another case of myth versus reality. . . . The stereotype western hero

is at least six feet, sometimes taller, and is sometimes said to have been

a former cavalry officer. But we are told the US regular cavalry had a

maximum height limit of 5 feet 10 inches. Some cavalry officers who were

state-raised militia, or men who raised their own regiments during the

Civil War, were big men, but regular cavalrymen were supposed

to be 5 feet 10 or less. The late John Wayne often portrayed a cavalry

officer in movies, yet at 6 feet 5 inches he would have been much too big

for the regular cavalry. The average man of the era would have stood about

5 feet 8 inches if Civil War records are taken to be a guide. And though

some Indians were tall, most were smaller than white men.

|

Role sized up.

Role sized up.

|

Hillerman: clouds

Hillerman: clouds

part.

|

In a Western Writers of America press release, award-winning

mystery writer Tony Hillerman said, "Western writing, to me is

when you're flying from the east and clouds block the view. You can't

see a thing. Then, you're over west Texas. The clouds part and what

do you see? Endless miles of sunshine and wide open spaces." WWA said

that over the past few decades, western literature had slid into an

abyss of reader apathy, but they were now facing a promising future.

Purchases of westerns in the United States increased 9 per cent in 2005

and 10 per cent in 2006. Publishers representative Larry Yoder said

today's westerns weren't what your grandfather read or "some TV show with

a predictable plot". WWA president Cotton Smith added stirringly,

"Western literature is of the spirit, our spirit, the spirit of America.

Western literature is the motivation of people to succeed in lands greater

than themselves. The Western is full of souls filled with concern, fear,

joy and desire. In a phrase, it is the literature of America's soul." Wow!

Remember that next time someone dismisses the book you're reading or writing

as "just another shoot-'em-up".

|

|

|

Multi Spur Award winner Richard S. Wheeler, graciously given space

at Ed Gorman's new, improved blog, raised doubts about the sales

health of the western in response to the WWA release. After some debate,

he said, "The death throes of a major American literary genre have occurred

beneath the periscopes of the journalists of literature and the book world.

These people don't care about western fiction, and know their readers

wouldn't care either, which is why the genre is all but gone." Wheeler

queried sales figures that failed to "distinguish between books published

commercially and vanity books done by print-on-demand publishers". Two

of Wheeler's fine westerns have appeared as BHWs: Sam Hook

(December 1987) and Stop (April 1990). Ed Gorman westerns,

too, have been issued in BHW, British-market editions: Gundown

(February 1997) and Wolf Moon (July 1998). For western readers

whose foremost requirement is a brisk and lively read, the blog debate furnished

extra reasons for western readers to support the Hale (and hopefully hearty)

series with purchases and library borrowings of the newest titles.

|

Wheeler: clouds gather.

Wheeler: clouds gather.

|

Ike's endorsement.

Ike's endorsement.

|

Never underestimate western fans. Paddy Gallagher (aka Greg Mitchell)

reminded Hoofprints that General, later US President Dwight D. Eisenhower

was an avid follower of westerns and his favourite movie was The Big

Country. "To broaden the scope of the books, the publishers should

be aiming higher and breaking new ground," Paddy said. "The most positive

feedback I got from my first BHW, Outlaw's Vengeance, came

from a well educated bloke I know who had never read a western in his life.

He read the book only because he knew me -- but he enjoyed the western atmosphere

so much, he was going to read more by other authors." Paddy, who lives near

Canberra, Australia, is currently working on completing his latest western

for a New York publisher, who responded to material held for a considerable

time. "It seemed to have disappeared off the face of the earth. . . . Then,

out of the blue, a letter arrived saying they liked what I had sent over

and would be interested in seeing the rest."

|

|

|

BHW writer Paul Wheelahan is known in his native Australia as a

comic-strip artist -- creator of The Panther (1957-63) --

and as the author of countless Cleveland western paperbacks under pen-names

including Brett McKinley, Emerson Dodge and Ben Jefferson.

His first BHW, Branded!, appeared under his own name in September

2000 and was followed by several more. Then, like prolific compatriot

Keith Hetherington who'd already joined the Hale camp, Paul adopted a

string of bylines: Dempsey Clay, Matt James, Ryan Bodie, Ben Nicholas

and Chad Hammer. Fellow author David Whitehead says, "One of the tricks Paul employed back

in his Cleveland days was to write the last of ten chapters first. Then,

if he found that the story was taking longer than anticipated to tell, he

could cut and compress it somewhere around the middle, thus avoiding the

usual problem of having a rushed ending." Paul's latest BHWs are Just

Call Me Clint by Chad Hammer and Gun Lords of Texas

by Matt James.

|

Last chapter first.

Last chapter first.

|

Reality for SF writer.

Reality for SF writer.

|

Western readers and writers were reminded that not all genres are fortunate enough to have a BHW series. Leo Stableford commented to blogger Grumpy Old Bookman, who'd written about the difficulties facing the genre writer, "This is possibly the best post I have ever read in any blog

ever on the topic . . . My father is a mid-list SF writer and academic and only started to have anything

like a career when the number of novels he'd written approached the late 40s

or early 50s (I really don't remember). Unfortunately, in today's world he didn't sell as was required, and now finds

securing a publisher impossible in the mainstream and challenging elsewhere.

He'd never even have got a foot in the door had he been born 30 years after

he was."

|

|

|

Greg Mitchell dispels misconceptions

ENDING WITH A BANG

. . . as Joshua

left the house's enclosure, the fleeing woman turned. In her hand, as if by

magic, there appeared a revolver.

It was a big, hefty piece of armament, with a barrel about nine inches

long. Joshua's expert eye placed it, possibly, as an old Walker Colt which

in total length would measure more than fifteen inches. Not exactly a lady's

pistol, Joshua thought, and forged on relentlessly.

"Stop!" he ordered. "That ancient piece of hardware will be useless

to you."

Sons

and Gunslicks

Chap O'Keefe

THE Walker Colt .44 revolver is a great favourite with western writers and

was the preferred weapon of many fictional gunslingers. But in real life,

it owed any popularity it gained to the fact that it had no competition.

Its predecessor, the Paterson Colt, was patented about 1836 and was the

first practical revolver. The Paterson revolutionized the handgun world but

it had its limitations. It was not a particularly robust arm with the choice

of five shots in calibres .28, .31,.34 and .36. The cap-and-ball, percussion

revolver was slow to load with loose powder, balls and percussion caps. If

the chambers were not sealed with grease or beeswax, the balls could be jolted

loose when carried muzzle-down on a horse, though the advantage of having

multiple shots outweighed the disadvantages.

The public at large did not receive Samuel Colt's revolving handgun with

enthusiasm. Colt ran into financial problems and he had to close his factory

at Paterson, New Jersey.

Among those who were quick to appreciate revolvers could be counted the

Texas Rangers. They used them against hostile Comanche warriors and Mexicans

to great effect. But they saw that improvements were needed. Consequently,

Captain Sam Walker approached the Colt company with ideas for an improved

revolver. The new weapon, produced for the rangers in 1847 and designated

the Walker Colt, was a radical departure from the Paterson but a much more

practical weapon.

The cylinder capacity was increased to six chambers, each capable of accommodating

more than 40 grains of powder and a .44 bullet. A conventional trigger guard

replaced the Paterson's folding trigger and a rammer attached under the barrel

ensured that the bullets were firmly seated in the chambers. The weapon was

heavy, slightly more than four and a half pounds in weight but that helped

to reduce the recoil from its powerful loads.

Colt arranged with the Whitney Armoury at Whitneyville, Connecticut, to manufacture

the new revolver. The factory produced 1,100 Walkers and they were the most

powerful handguns of the day. The profit Colt made was enough to set him

up in new headquarters at Hartford.

Glowing contemporary reports claim that the Walker was more effective than

the "common rifle" at 100 yards and more accurate than the smoothbore musket

at 200 yards. The claims should not be taken at face value. Much depends upon

the definition of the "common rifle". The same weight of bullet and the same

powder charge would generate much more speed and energy in the longer rifle

barrel, as the famous Winchester '73 later demonstrated. The Walker fired

a rifle-sized charge but in the shorter barrel could not match rifle ballistics

for similar loadings. It was more accurate than the musket at 200 yards because

its barrel was rifled. The smoothbore musket had little accuracy beyond 90

yards. Uneven gas escape from around the ball sent the bullet astray. A musket

ball might travel a fair distance if the right elevation was given to the

weapon but long-range accuracy was out of the question.

Many early Colts were sighted to hit the point of aim at 60 yards so inside

that range they shot a little higher. Given the right elevation of the barrel

their extreme range was about 1,400 yards but both power and accuracy would

be lacking by then.

The Walker's large powder capacity was also its downfall. Some claim that

as much as 50 grains of powder could be crammed into the chamber although

the recommended charge was 40 grains. Of the 1,100 Walkers produced, approximately

300 were said to have blown up as a result of cylinder failure. It had been

the most powerful revolver of its day but the day was a short one.

Colt rapidly improved the Walker to produce the Colt Dragoon which was lighter,

better balanced, and with superior craftsmanship and materials. It could still

fire a 40 grain powder charge. After three models of Dragoon, the last big-bore

Colt percussion revolver was the streamlined 1860 .Colt Army. It still

fired a .44 bullet but the powder charge was reduced to 28 grains. This gun

was noted for its easy pointing and accuracy. Because of patent problems,

Colt could not start producing metal-cartridge revolvers loading through

the rear of the cylinder until 1871.

Percussion revolvers quickly went out of favour. They were unreliable and

difficult to load when compared with the newer types.

Was the Walker ever a gunfighters' gun? It was only when nothing better

was available. The length and weight made it an ungainly weapon unsuited to

quick draws and the arm lacked the natural pointing ability that was a feature

of later Colt revolvers. It was obsolete before the American Civil War.

Carrying ammunition for percussion revolvers was always a problem. At first

the shooter had to carry a small flask designed to deliver a measured charge

of powder, loose bullets and a supply of percussion caps. Some also carried

a small quantity of grease to seal the mouths of the chambers to keep the

powder dry and to avoid chain fires. Later, combustible paper cartridges containing

measured powder charges were attached to the bullets but these were prone

to damage that made them difficult to load. The cavalry carried these cartridges

in wool-lined pouches to prevent them being damaged. But separate percussion

caps still had to be added before the weapon could be fired.

By 1870 metallic cartridges had proved their worth and percussion weapons

were being phased out. Revolvers like the Walker took too long to load and

had a high rate of misfires. They also had the disconcerting habit of "chain

firing" when all chambers discharged at once. This fault also sounded the

death knell of the Colt revolving rifle. A man holding a revolving rifle in

the conventional manner could lose all or part of his left hand if the weapon

chain fired. The only safe way to hold a Colt revolving rifle was for the

left hand to hold the front of the trigger guard. They were considered so

dangerous that they were withdrawn from Union troops during the Civil War.

In 1873, the Winchester company brought out the improved, centrefire version

of their popular 1866 repeating rifle. The cartridge was designated the .44/40.

and fired .44 bullets propelled by 40 grains of powder. This was a similar

load to that fired by the Walker Colt. The Colt company in the same year

introduced the famous .45 calibre, Frontier Colt. Then in 1876, Colt started

chambering Frontier Colts for the .44/40 cartridge so a man could use the

same ammunition in both rifle and revolver. In a revolver, the .44/40 had

marginally less hitting power than the Colt .45.

A gunfighter who continued using percussion arms after 1873 was certainly

flirting with the hurting. Although Wild Bill Hickok had a pair of .36 Navy

Colts, he was thought to have possessed metallic cartridge weapons, too. The

James Brothers, the Earps, Bill Cody, Bat Masterton and Billy the Kid Pat

Garrett and a host of outlaws all used metal-cartridge revolvers. There would

be little demand for a weapon as unreliable and outdated as the Walker Colt.

The Walker was an important development in revolver design but did not deserve

the legendary status that some writers later gave it. Lightning draws and

trick shots were out of the question with these weapons but if they hit a

man, he stayed hit.

-- Paddy Gallagher, aka BHW

writer Greg Mitchell

|

Paterson factory

Paterson factory

Sam Walker

Sam Walker

Sam Colt

Sam Colt

Dragoon

Dragoon

Army

Army

Frontier

Frontier

Wild Bill Hickok

Wild Bill Hickok

|

|

The Extra pays tribute to Sydney J. Bounds

FAREWELL TO A SMALL GIANT

Jess Harper sat

alone on a pine bench outside his rough-hewn log cabin, waiting. Behind

him, the late afternoon sun sank beyond the rim of the canyon, and the

cabin gave him shade. The air was stifling hot, dry, and the yard inch-thick

with dust.

Short and broad, Harper had the solid build of a grizzly, his hair

touched early with iron-grey. His rugged, almost homely, face showed lines

of stubbornness.

Lynching at Noon City

Sydney J. Bounds

FOR discerning readers of BHWs, 2006 ended sadly with news of the death,

on November 24, of veteran author Sydney J. Bounds, aged 86.

I knew Syd in London in the 1960s and had huge respect for him as

one of the most versatile workers in the genre-fiction business -- SF,

detective, western, horror, plus scripts for war libraries and even nursery

comics. Quietly spoken, small in stature, non-assertive, he was the true

professional. Editorially, I had the pleasure of handling his work at

Fleetway House, for the Sexton Blake Library detective series, at Micron

Publications, for the Edgar Wallace Mystery Magazine, and at Odhams Books,

for various boys' adventure annuals.

Editors and publishers continued to hold him in esteem. My sentiments echo

those of John Hale, chairman and managing director of Robert Hale Ltd.

"I am sure he was the oldest author on the BHW

list. I cannot remember ever having had personal contact with him direct,

as in recent years all his work came to us via an agent. However, my recollection

is entirely of an unassuming and highly professional author who could turn

his hand to all sorts of fiction writing."

|

|

|

Even as the office junior at Fleetway, I recognized Syd was much

under-rated. His Sexton Blake novels were published as by Peter Saxon,

George Sydney and Desmond Reid -- all "house" pen-names -- but my memory

is that the re-write work on them was barely necessary. When a Blake novel

was later chosen to be serialized for the first time in a widely circulated

weekly paper, Tit-Bits, it came as no surprise to me that

it was one of Syd's. I've heard, though, that the unassuming Syd wasn't

told and found out only much later.

Sydney James Bounds was born on November 4, 1920 in Brighton, a seaside

resort fifty miles south of London. He worked as an electrical fitter before

moving to Kingston-on-Thames, where he studied electrical engineering at

a technical college. During World War II, he was an electrician and instrument

repairer for Royal Air Force ground crew. At the same time, he began writing

science fiction and fantasy.

Steve Holland, at his aptly named blog, Bear Alley, records that

Syd sold his first story in 1943 and was one of the more prolific authors

of the "mushroom jungle" post-war era of cheap UK paperback publishing.

Steve says, "Although he wrote over 40 novels, Syd’s metier was always the

short story of which he wrote hundreds, many published anonymously in children’s

papers and annuals. Anyone who has tried to make a living from selling

fiction will know the difficulties of changing characters and plots every

2,000 words, yet Syd managed to make a living doing just that for many years.

Although best known for his science fiction, his talent for turning a situation

on its head in one chilling line made him one of the champions of small

press horror magazines of the 1980s and 1990s."

|

|

|

Among Syd's earlier work, was a string of western novels in the 1950s

for the Amalgamated Press's Western Library as James Marshal. In the 1960s,

he wrote more westerns under his own name for Robert Hale Ltd. These were of the same length

as, and appeared in a similar format to, the later Black Horse Westerns.

Titles I know of were The Yaqui Trail, Gun Brothers and

Lynching at Noon City.

In the spring of 2000, Syd began writing westerns for Hale again after

literary agent Phil Harbottle sold many of his old paperback westerns to

the firm for reissue in BHW hardcover.

The reissues came out under a baffling

variety of pen-names: Howard Baron, Alexander Black, Roger Carne, Richard

Daniels, Sam Foster, Jack Greener, David Guest, Paul Hammond, David Somers,

Wes Sanders, Will Sutton, Neil Vaughan and Cliff Wallace. The new books appeared under

the remarkable octogenarian's own byline.

One book was quickly picked for publishing in the Linford Western

Library large-print series, making it more readily available everywhere,

including the US.

|

|

|

Savage's Feud was a slam-bang episode in the life of

Syd's series hero, Savage. The feud involved two families, the Howards

and the Flints, and had its origins in the Civil War. At stake was a small

fortune built on a stolen Army pay chest. Also quickly on the line were

various lives, including Savage's.

Though not the first book in the Savage series, Syd's well-honed

storytelling skills made it possible for the reader to piece together

quickly, from allusions in the opening pages and later, that Savage was

a young delinquent from the New York waterfront working as a Pinkerton agent

in the South-west. He was referred to frequently as "small". But his appearance,

of course, deceived -- an attribute he shared with many of the Max Brand

heroes of olden times. Savage was as ferocious as his name. "A strong name,"

said the Indian Little Owl.

At one stage, after a bloody knife-duel to the death, another character

stared at Savage and asked, "Do the Pinkertons have any idea what kind

of animal they've hired?" Savage replied, "Mr Allan [Pinkerton] picked

me himself."

After decades at the action-fiction coalface, Syd's style was as

terse and uncomplicated as ever in this yarn: "He walked up rising ground

to where the house sat on the crest. Lights in the windows were like eyes

watching him. The sky darkened and horses in the corral turned their heads

to stare as he passed by. No doubt there were men behind watching too."

And Syd still had the happy knack of sketching a gallery of colourful

characters, even minor ones, with a few well-chosen words. Thus of a town

marshal: "Even if he did have a wave in his hair and his guns had pearl

handles, they still had real bullets in them." And "The storekeeper gave

a weak smile. He was called the Pope because he wore a stiff collar and

refused to open his shop on Sundays."

The arch-villain was a greedy and self-seeking town boss, as well

as a fanatical ex-Confederate. Wheelchair-bound, he charged at the finale

with a wild Rebel yell and a cavalry sword of good Southern steel extended

before him. "This time, Savage, you're a dead man!"

Another Savage title, A Man Called Savage -- the first --

will be reissued in a Linford large-print edition this (northern) summer.

The latest (last?) BHW is scheduled for May and is also a Savage story

-- Savage Rides West.

Unmarried, Syd lived at the same address, 27 Borough Road, Kingston-on-Thames,

for more than forty years. Like Steve Holland, I can still remember it

from the '60s on editorial correspondence and the cover sheets to his neatly

typed, always tidy manuscripts. Last May, however, he moved to Telford,

Shropshire. Diagnosed with terminal cancer, he was admitted to a hospice and died just a few weeks after his 86th birthday.

-- Keith Chapman

|

|

|

Literary researcher STEVE HOLLAND holds a special regard

for Sydney J. Bounds. He explains why in this personal Appreciation:

What can I say about Syd? He was a real gentleman and one of the first

authors I ever contacted, way back in 1979 when I was still at school. I

had to do a project for one of our classes, a kind of General Studies class,

where we could choose any subject at all. I chose British SF magazines,

because I'd then recently become interested in them.

Through people like Phil Harbottle and Mike Ashley, I was able to contact

some of the folks involved in the SF mags of the 1940s, one of whom was

Syd. Later, when I had the crazy notion of putting together a small mag,

Syd contributed a story. My project came to nothing, but I did subsequently

publish one of Syd's stories in a souvenir booklet produced for the first

Paperback & Pulp Bookfair.

Syd attended all the book fairs and turned out to be as friendly and generous

in person as he was in correspondence. We talked about his long career as

a writer, usually about his SF stories, or the stories that had appeared

in annuals, or maybe the comic strips he'd penned -- whatever I happened

to be researching at the time.

Because Syd was a professional, he could

turn his hand to any genre and succeed. I don't mean to imply that he was

a hack who would simply go where the money was being offered, although all

professionals are forced to do that to a degree. He didn't have the hack

mentality. He wouldn't just rehash some old idea dressed up as something

new. . .he always tried to bring something new to everything he wrote that

could often turn a stock situation on its head. He was also a very good

writer of twist-in-the-tail short stories. Unlike the true "hack writer",

Syd wouldn't short-change his readers.

Perhaps that has something to do with the fact that Syd enjoyed meeting and

talking to people he knew would be reading his stories. From his early days

in science fiction fandom in the 1930s to his final years in what is now

the 21st century, Syd was regularly face-to-face with his audience. Perhaps

that's what made him want to put in that little bit extra and take just

a little more care with his writing than some of his contemporaries.

Writing is what he did and he was very pleased to be back in the saddle with

his Black Horse Westerns. At the age of 79 he took on what was initially

a five-book deal. Towards the end, he would say he was thinking about retiring .

. . but then he'd write another book, and another, and another. . . . By the

end he had written over a dozen new novels in half as many years, and not

one of them shows any lessening of his ability to tell a damn good story.

Farewell, Syd.

|

|

|

|

|

|

NEW

BLACK HORSE

WESTERN NOVELS

(Published by Robert Hale Ltd, London)

978

Buried Guns

|

Dan Claymaker

|

0 7090 8247 7

|

Moon Raiders

|

Skeeter Dodds

|

0

7090 8253 8

|

Just Call Me Clint

|

Chad Hammer

|

0

7090 8252 1

|

Zacchaeus Wolfe

|

P. McCormac |

0

7090 8243 9

|

Gold Country Ambush

|

George X. Holmes

|

0

7090 8257 6

|

| Dalton's Valley |

Ed Law

|

0

7090 8264 4

|

Montana Keep

|

Billy Hall

|

0

7090 8263 7

|

They Called Him Lightning

|

Mark Falcon

|

0

7090 8267 5

|

The Range Shootout

|

Carlton Youngblood

|

0

7090 8216 3

|

Brevet Ridge

|

Abe Dancer

|

0

7090 8275 0

|

Sons and Gunslicks

|

Chap O'Keefe |

0

7090 8068 8

|

The Long Trail

|

Corba Sunman |

0

7090 8127 2 |

Bluecoat Renegade

|

Dale Graham

|

0

7090 8166 1

|

Killer on the Loose

|

Elliot Long |

0

7090 8300 9

|

Texas Rendezvous

|

Gary Astill

|

0

7090 8302 3

|

| Hideout

|

Eugene Clifton

|

0

7090 8308 5

|

Flight from Felicidad

|

Steven Gray

|

0

7090 8315 3

|

Satan's Gun

|

Bill Williams

|

0

7090 8316 0

|

The Vernon Brand

|

Tom Benson |

0

7090 8317 7

|

The Laredo Gang

|

Alan Irwin |

0

7090 8318 4

|

Showdown at Trinidad

|

Daniel Rockfern

|

0 7090 7649 0

|

Hell Pass

|

Lance Howard

|

0 7090 8187 6

|

Both Sides of the Law

|

Hank J. Kirby

|

0 7090 8307 8

|

Kid Lobo

|

Clayton Nash

|

0 7090 8322 1

|

Gun Lords of Texas

|

Matt James

|

0 7090 8323 8

|

The Mavericks

|

Mark Bannerman

|

0 7090 8324 5

|

The Man They Couldn't Hang

|

Scott Connor

|

0 7090 8336 8

|

Dangling Noose

|

Jack Holt

|

0 7090 8337 5

|

Draw Down the Lightning

|

Ben Bridges

|

0 7090 8340 5

|

Silver Galore

|

John Dyson

|

0 7090 8355 1

|

|

|

|

Ten new titles are

issued every month as BHWs -- tough, traditional or,

sometimes, off-trail. The brand caters for all tastes.

Black

Horse Westerns can be requested at public libraries, ordered at bookstores,

and bought online through the publisher's website, www.halebooks.com, or retailers including Blackwells, Amazon UK, WH Smith and VinersUK Books.

Trade inquiries

to: Combined Book Services,

Units I/K, Paddock Wood Distribution

Centre,

Paddock Wood, Tonbridge, Kent TN12 6UU.

Tel: (+44) 01892 837 171 Fax: (+44)

01892 837 272

Email: orders@combook.co.uk

|

|

|

|

|

|